In a landmark public health finding, a new study from the Harvard School of Public Health finds that carbon dioxide (CO2) has a direct and negative impact on human cognition and decision-making. These impacts have been observed at CO2 levels that most Americans — and their children — are routinely exposed to today inside classrooms, offices, homes, planes, and cars.

Carbon dioxide levels are inevitably higher indoors than the baseline set by the outdoor air used for ventilation, a baseline that is rising at an accelerating rate thanks to human activity, especially the burning of fossil fuels. So this seminal research has equally great importance for climate policy, providing an entirely new public health impetus for keeping global CO2 levels as low as possible.

In a series of articles, I will examine the implications for public health both today (indoors) as well as in the future (indoors and out) due to rising CO2 levels. This series is the result of a year-long investigation for Climate Progress and my new Oxford University Press book coming out next week, “Climate Change: What Everyone Needs to Know.” This investigative report is built on dozens of studies and literature reviews as well as exclusive interviews with many of the world’s leading experts in public health and indoor air quality, including authors of both studies.

What scientists have discovered about the impact of elevated carbon dioxide levels on the brain

Significantly, the Harvard study confirms the findings of a little-publicized 2012 Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) study, “Is CO2 an Indoor Pollutant? Direct Effects of Low-to-Moderate CO2 Concentrations on Human Decision-Making Performance.” That study found “statistically significant and meaningful reductions in decision-making performance” in test subjects as CO2 levels rose from a baseline of 600 parts per million (ppm) to 1000 ppm and 2500 ppm.

Both the Harvard and LBNL studies made use of a sophisticated multi-variable assessment of human cognition used by a State University of New York (SUNY) Upstate Medical University team, led by Dr. Usha Satish. Both teams raised indoor CO2 levels while leaving all other factors constant. The findings of each team were published in the peer-reviewed open-access journal Environmental Health Perspectives put out by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, a part of NIH.

The new study, led by Dr. Joe Allen, Director of Harvard’s Healthy Buildings program, and Dr. John Spengler, Professor of Environmental Health and Human Habitation at Harvard, used a lower CO2 baseline than the earlier study. They found that, on average, a typical participant’s cognitive scores dropped 21 percent with a 400 ppm increase in CO2. Here are their astonishing findings for four of the nine cognitive functions scored in a double-blind test of the impact of elevated CO2 levels:

The researchers explain, “The largest effects were seen for Crisis Response, Information Usage, and Strategy, all of which are indicators of higher level cognitive function and decision-making.” The entire article is a must-read as is the LBNL-SUNY study.

NASA has also observed CO2-related health impacts on International Space Station (ISS) astronauts at much lower CO2 levels than expected and has identified a mechanism by which CO2 levels could affect the brain, as I will discuss in Part 2. As a result, NASA has already lowered the maximum allowable CO2 levels on the space station. The ISS crew surgeon who is the lead for studying the impact on astronauts of CO2 (and other gases) told Climate Progress he considers the original LBNL-SUNY study “very credible.” Indeed, NASA itself is now starting terrestrial studies to look at the impact of CO2 on judgment and decision-making for the astronaut cohort — and it is partnering with the same SUNY team of behavioral psychologists.

All of this new research is consistent with — and actually helps explain — literally dozens of studies in the past two decades that find low to moderate levels of CO2 have a negative impact on productivity, learning, and test scores. See here for a research note and bibliography of some 20 studies and review articles.

The impact of fossil fuels and modern buildings on human cognition

For most of human evolution and modern history, CO2 levels in the air were in a fairly narrow and low range of 180 to 280 parts per million. Also, during the vast majority of that time, humans spent most of their time outdoors or in enclosures that were open (like a cave). Even once humans built dwellings, those were not tightly sealed as modern buildings are. So even though we generate and breathe out CO2, homo sapiens were not generally exposed to high, sustained CO2 levels.

But in recent decades, outdoor CO2 levels have risen sharply, to a global average of 400 ppm. Moreover, measured outdoor CO2 levels in major cities from Phoenix to Rome can be many tens of ppm higher — up to 100 ppm or more — than the global average. That’s because CO2 “domes” form over many cities primarily due to CO2 emissions from traffic and local weather conditions.

The outdoor CO2 level is the baseline for indoor levels. In buildings — the places where most people work and live — CO2 concentrations are considerably higher than outdoors. CO2 levels indoors that are 200 ppm to 400 ppm higher than outdoors are commonplace — not surprising since the design standard for CO2 levels in most buildings is 1000 ppm. In addition, that differential increases when more people are crammed into a space and when the ventilation is not adequate. As the Harvard researchers point out, in recent decades, buildings have become more tightly sealed, and there has been less exchange of inside air with fresh outside air.

How high can CO2 levels get indoors? As but one salient example, the 2012 LBNL-SUNY article notes, “In surveys of elementary school classrooms in California and Texas, average CO2 concentrations were above 1,000 ppm, a substantial proportion exceeded 2,000 ppm, and in 21% of Texas classrooms peak CO2 concentration exceeded 3,000 ppm.” In Part 3, I’ll look at the extensive literature on the relationship between high classroom CO2 levels and poor student performance — and the simple strategies Indoor Environmental Quality experts say that parents, teachers, and school administrators should be doing now to address this serious problem.

Yet, the vast majority of studies linking CO2 levels to poorer performance at work and school merely used CO2 as a measure of ventilation rates and indoor air quality (since monitoring CO2 levels is relatively cheap and easy). As the LBNL-SUNY study notes, “It has been widely believed that these associations exist only because the higher indoor CO2 concentrations occur at lower outdoor air ventilation rates and are, therefore, correlated with higher levels of other indoor-generated pollutants that directly cause the adverse effects,” such as volatile organic compounds and particulates.

As a result, “CO2 in the range of concentrations found in buildings (i.e., up to 5,000 ppm, but more typically in the range of 1000 ppm) has been assumed to have no direct effect on occupants’ perceptions, health, or work performance.” In short, CO2 had not been a suspect in the negative impacts measured in all these studies. Indeed one of the authors of the LBNL-SUNY study, Dr. William Fisk, leader of LBNL’s Indoor Environment Group, told me that he was surprised when the testing showed significant impacts from just raising CO2 indoor CO2 levels 400 ppm.

Yet very few of those other studies offered a specific mechanism for the negative impacts they measured beyond hand-waving assertions of “inadequate indoor air quality.” With the recent work from the Harvard, LBNL, SUNY, and NASA researchers, however, we now have at least a partial answer to the mystery, according to several experts I spoke to: High CO2 levels don’t merely serve as an indicator of poor air quality that causes occupants problems, they are actually one cause of those problems.

Interestingly, the authors of all of these studies — the direct CO2 studies and the CO2-as-a-proxy-for-ventilation studies — are generally public health researchers focused on indoor environmental quality (IEQ). As a result, their published work does not examine the implications these findings have for climate policy.

The risks of doing nothing

But the implications for climate policy are stark. We are at 400 parts per million (ppm) of CO2 today outdoors globally — and tens of ppm higher in many major cities. We are rising at a rate of 2+ ppm a year, a rate that is accelerating. Significantly, we do not know the threshold at which CO2 levels begin to measurably impact human cognition.

The LBNL study found a measurable negative impact on human cognition at 1000 ppm. The Harvard researchers had a more comprehensive study that found significant negative impact at 930 ppm. Moreover, many measurements made by the Harvard team point to a much lower threshold, as the top figure shows. Equally important, the researchers found “The exposure-response between CO2 and cognitive function is approximately linear across the concentrations used in this study.” So the impact threshold may be quite below 930 ppm. Clearly more research needs to be done to solve this detective story.

he latest IEQ research does offer strong suggestions that the threshold could be near (or possibly even below) levels the entire world could experience outdoors over the next hundred years — levels that are essentially irreversible for centuries.

As one clue to where that threshold may be, we can turn to recent research from Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) for the U.S. General Services Administration, which found a threshold of about 600 ppm. At 1,282 workstations in 64 diverse buildings across the country, CMU measured CO2 levels and surveyed occupancy perception of air quality.

The result: “An in-depth analysis reveals that occupant satisfaction with overall air quality is strongly linked to CO2 levels, with significant shifts to satisfaction when CO2 is less than 600 ppm.” That’s from an as-yet unpublished CMU thesis “Are Humans Good Sensors? Using Occupants as Sensors for Indoor Environmental Quality Assessment and for Developing Thresholds that Matter,” for a Ph.D. in “Building Performance and Diagnostics.”

I spoke to the chair of the thesis committee, Vivian Loftness — University Professor and former Head of the School of Architecture — one of the world’s leading experts on “Health, Productivity, and the Quality of the Built Environment,” which is a graduate course she teaches. Over the last quarter century, she has assembled the most extensive database in the world of studies on the health and productivity gains from green building design. I first met her when I was working on a book of case studies on that very subject in the late 1990s.

Loftness, who oversaw the GSA study, explained that CMU’s analysis showed that “humans are pretty good sensors of high CO2 levels.” Occupant perception of indoor air quality drops sharply as CO2 levels rise from 600 to 750 ppm.

She is familiar with the recent work showing a direct link between CO2 and human cognition. She said of the original LBNL-SUNY study, “a seminal piece of work and a great research team.” She considers the Harvard study “an absolutely important study.”

Loftness draws two key conclusions from these studies, her own work, and the vast database of scientific literature she has surveyed. First, the immediate public health message is to increase ventilation and the use of outside air in buildings. And second:

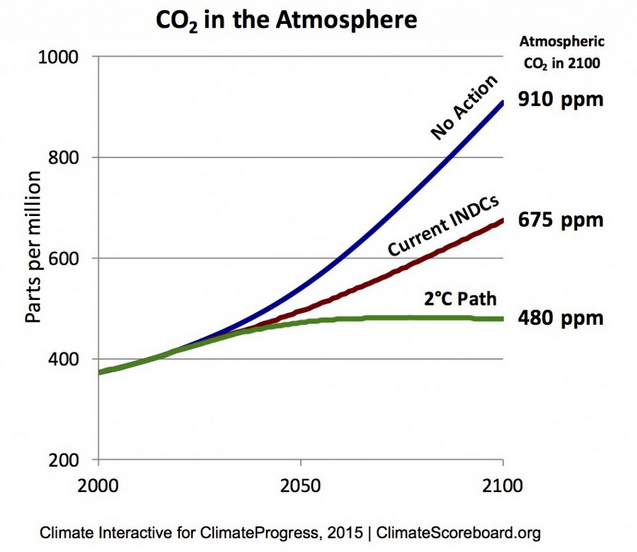

We have to do everything we can to keep outdoor CO2 levels below 600 ppm because something serious starts happening then.Researchers at Climate Interactive put together a chart of where CO2 levels headed as we head into the crucial Paris climate talks in December.

Success at Paris, as I have written, would buy us 5 to 10 years in the fight to avoid catastrophe. But we would still be on a path to 675 ppm, which is too high for both the climate change impacts and the direct human cognition impacts. Worse, that level of warming will likely trigger many major carbon-cycle amplifying feedbacks that are not included in the climate models, such as permafrost melting. So we must take stronger action.

On the immediate public health front, we need to start monitoring indoor CO2 more closely and keep inside levls as close as possible to levels outdoors through greater use of outside air. According to the building design experts I have interviewed, such as Dr. Loftness, that can be done without increases in building energy consumption using cost-effective strategies and technologies available today. Indeed, systematic green design will lower total energy consumption. I will examine these design strategies later in this series.