Poor air quality kills 1.2 million people in India every year. To help battle that staggering statistic the Indian government is instituting a plan to help get fossil fuel powered vehicles off the road. The plan calls for the end of gas powered vehicle sales by 2030.

|

| In India, almost as many people die from air pollution as cigarette smoke. Image: REUTERS/Rupak De Chowdhuri |

It’s hoped that by ridding India’s roads of petrol and diesel cars

in the years ahead, the country will be able to reduce the harmful

levels of air pollution that contribute to a staggering 1.2 million deaths per year.

India’s booming economy has seen it become the world’s third-largest oil importer, shelling out $150 billion annually for the resource

– so a switch to electric-powered vehicles would put a sizable dent in

demand for oil. It’s been calculated that the revolutionary move would save the country $60 billion in energy costs by 2030, while also reducing running costs for millions of Indian car owners.

|

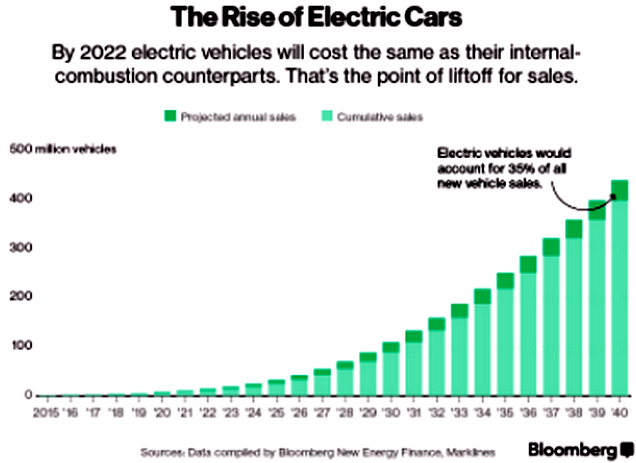

| Image: Bloomberg |

|

| Image: Shutterstock |

More than a million people die in India every year as a result of breathing in toxic fumes, with an investigation by Greenpeace finding that the number of deaths caused by air pollution is only a fraction less than the number of smoking-related deaths.

The investigation also found that 3% of the country's gross domestic product was lost due to the levels of toxic smog.

In 2014, the World Health Organization determined that out of the 20 global cities with the most air pollution, 13 are in India.

Efforts have been made by the country’s leaders to to improve air

quality, with one example coming in January 2016 when New Delhi’s

government mandated

that men could only drive their cars on alternate days depending on

whether their registration plate ended with an odd or even number

(single women were permitted to drive every day).

While such interventions have enjoyed modest success, switching to a

fleet of purely electric cars would have a much greater environmental

impact.

Indeed, it’s been calculated that the gradual switch to electric vehicles across India would decrease carbon emissions by 37% by 2030.

Oil firms facing uncertain future

Oil firms facing uncertain future

As India’s ambitious electric vehicle plans begin to take shape,

oil exporters will be frantically revising their calculations for oil

demand in the region.

In its report into the impact of electric cars on oil demand,

oil and gas giant BP forecast that the global fleet of petrol and

diesel cars would almost double from about 900 million in 2015 to 1.7

billion by 2035.

|

| Image: BP |

|

Image: EVvolumes.com

|

Almost 90% of that growth was estimated to come from countries that

are not members of the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development), such as India and China.

China is also gearing up for a move away from gas-guzzling cars.

Last month, the Chinese confirmed they intend to push ahead with plans that will see alternative fuel vehicles account for at least one-fifth of the 35 million annual vehicle sales projected, by 2025.

Oil bosses claim it’s too early to tell what the implications of a

move away from petrol and diesel cars will be. However, Asia has long

been the main driver of future oil demand and so developments in India

and China will be watched extremely closely.

Links

Links

- Qantas spruiks electric vehicle era

- Number one argument against electric cars is now completely debunked

- UK car industry pins hopes on battery-powered electric vehicles

- Instantly rechargeable batteries are about to change everything!

- The Country Adopting Electric Vehicles Faster Than Anywhere Else

- China Is Leading The World's Boom In Electric Vehicles -- Here's Why

- Electric Vehicles Are Cleaning Up