The Guardian - Adam Morton

Special report: The pace of coal plants shutting down in Australia could mean the country’s fleet could be gone before 2040. The transformation is enormous – and seems inevitable

F

For

a glimpse into the future of coal power in Australia, go west. The

country’s last major investment in coal-fired electricity was in Western

Australia in 2009, when Colin Barnett’s state government announced a

major refurbishment of the

Muja AB station about 200km south of Perth, far from the gaze of the east coast political-media class.

The plant was 43 years old and mothballed. Reviving it was meant to

cost $150m, paid for by private investors who would reap the benefits

for years to come. But costs and timeframes blew out. An old corroded

boiler exploded. The joint venture financing the project collapsed; a

wall followed suit. The bill ultimately pushed beyond $300m, much of it

to be stumped up by taxpayers – and once completed, the plant was beset

with operational problems. It ran only 20% of the time.

By April 2016, the government acknowledged it was subsidising more

generation capacity than it needed and predicted demand for coal power

would fall over the coming decade. In May this year the new Labor

administration confirmed Muja AB would shut early next year.

The coal-fired power sector is in free fall, and wind and solar are competing on cost with fossil fuels

Simon Holmes à Court, Energy Transition Hub

This spectacular failure had unique elements but underpinning it was a

faith in the longevity of coal-fired electricity. Though it rated

little mention in the east – mainly because WA is out of sight and has

its own grid separate to the mislabelled national electricity market –

it is a pointer to what lies ahead.

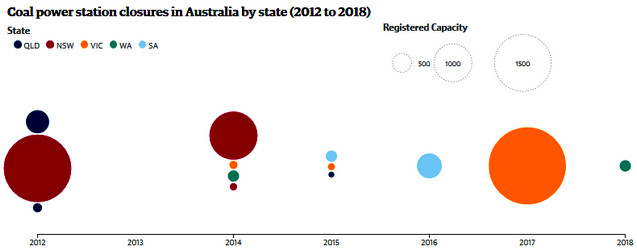

About a fifth of the country’s coal capacity has disappeared since

2012; Muja AB will be the 13th station to shut in that period; no new

ones have opened this decade. For all the talk of new coal-fired power

plants, none are in development.

If closures continued at the current rate, the nation’s coal fleet

would be gone before 2040. It’s a pace that could put Australia within

striking distance of what scientists say is necessary in the electricity

sector for the country to play its part in combating climate change. It

is far beyond what the government believes possible if the country is

to maintain a reliable and affordable electricity supply, and slower

than what some energy analysts think could happen given the

extraordinary advances in renewable energy cost and technology.

“The coal-fired power sector is in free fall, and wind and solar are

competing on cost with fossil fuels,” says Simon Holmes à Court, senior

adviser at the federally funded

Energy

Transition Hub at the University of Melbourne. “Every single panel and

turbine installed reduces the market size for inflexible baseload

plants.”

Industry insiders stress the scale of the transformation being discussed shouldn’t be downplayed.

Coal

still provides about three-quarters of our electricity. In the short

term, its withdrawal is likely to slow. Demand for power unexpectedly

fell at the start of the decade, leading to an oversupply that

suppressed the wholesale price of electricity. But with competition

reduced and expensive natural gas-fired plants being called on to carry

more of the load, the price is now as much as eight times the cost of

generation. The remaining coal plants are making hay.

That will inevitably change. After an investment strike a couple of

years ago, wind turbines and solar panels are going up in a rush to meet

the national 2020 renewable energy target. Once they come online by

mid-2019 competition will increase and, for a while at least, the

skyward rush of wholesale electricity prices should ease. What happens

to existing coal power plants at that point is an open question.

|

| Workers finish their last shift at Hazelwood power station on 31 March. Photograph: Scott Barbour/Getty Images |

Here is what we do know: coal generators usually operate for about

half a century and most Australian plants are pushing that age.

Yallourn, in Victoria’s Latrobe Valley, turns 50 in 2021. AGL has

already announced Liddell power station in New South Wales will close in

2022. A brace of others will hit their expected use-by dates in the

decade after 2025.

Analysis

by Holmes à Court suggests 15.1 gigawatts – nearly 10 times the

capacity of Hazelwood, the failing, old Victoria plant that shut in

March – could retire in that period. It would leave just 11 coal plants

with a maximum capacity less than a third of what was in place five

years ago. Most of those would be in Queensland, near the end of the

grid.

Meanwhile, between eight and 22 gigawatts of wind and large-scale

solar farms may have been built and 20 gigawatts of solar panels

installed on roofs, according to

Australian Energy Market Operator

projections. It’s possible generation capacity equivalent to

Australia’s entire east coast grid could have been built using variable

clean energy technology in just a couple of decades.

I don’t think the banking sector and the industry are looking to build coal-fired power stations

Matthew Warren, Australian Energy Council

In a

report on investment trends,

analysts at Bloomberg New Energy Finance projected that by 2040

small-scale solar power will have replaced coal as Australia’s largest

source of energy. They found 45% of electricity capacity would be

“behind the meter”, rather than from the traditional grid. Photovoltaic

panels, battery packs and demand response programs – cash incentives

offer to those who volunteer to cut use at peak times – would take over.

As Bloomberg New

Energy

Finance’s Australian chief, Kobad Bhavnagri, acknowledges, modelling in

this area will inevitably be wrong – but it indicates the direction.

Holmes à Court believes the system is at a turning point that few have

appreciated.

Here is what else we know: there is little to no interest in the

business community in building new coal plants to replace those that

shut. The

2015 Paris climate agreement

triggered a step change in thinking about the long-term viability of

fossil-fuel investments. Action towards meeting the Paris goals is

fitful but financiers are operating on the assumption policies will

escalate, including a probable eventual return to some form of carbon

pricing. They are in no mood to make a decades-long bet against it.

The Australian Energy Council chief, Matthew Warren, representing

most generators, summarised: “I don’t think the banking sector and the

industry are looking to build coal-fired power stations for the

foreseeable future.”

|

| Catherine Tanna, the managing director of Energy Australia. Photograph: Nikki Short/AAP

|

Coal is on the outer in other ways. As more variable renewable

generation is introduced into electricity grids, market operators are

increasingly

favouring flexibility over the traditional baseload model.

They see the future in generators that can swing in quickly on demand,

rather than run all the time. The government has agreed new wind and

solar photovoltaic farms will need to have “dispatchable” backup that

can be called on at any time, but coal is not as nimble as batteries,

gas, demand response or

concentrated solar thermal with storage.

It has been slow to filter through to some corners of the political

debate, but some business leaders have been stressing these points for

months. The specifics demanded vary but most want a bipartisan policy

that would provide the confidence to build new plants to replace closing

coal. The Business Council of Australia, representing more than 100

corporate leaders, has become increasingly bolshy. In a round table with

the Australian Financial Review last month the council’s board pressed

the government to adopt the chief scientist

Alan Finkel’s recommendation

to introduce a clean energy target, which would offer incentives on a

sliding scale, favouring plants with the lowest emissions.

Asked where coal fitted within that, the board member and Energy Australia managing director Catherine Tanna described it as a

“legacy technology” that was “very, very unlikely to find a market participant”

willing to pay for it. Tanna also called out as myth the idea that a

coal-fired power station using new technology would be cheap and lead to

a cut in electricity prices. “I just don’t think it’s borne out by the

economics,” she said.

The most regular argument made in response to this is: other

countries are building new coal stations and if the new technology is

good enough for China, Japan and Germany, why not Australia? The

Minerals Council of Australia is pushing hard for government funding for

next-generation technology, known as ultra-supercritical coal which,

according to a

2016 World Coal Association report,

creates emissions that are 23% lower than the black coal plants of NSW

and Queensland but is also 40% more expensive to build. Few fossil-fuel

proponents still use the term “clean coal” – mockery has stolen its

promotional punch, “clean coal” is a mirage – but when deployed it is

applied to new technology that reduces emissions.

What is 'clean coal' technology?

The term “clean coal” applies to two different technologies:

- Carbon capture and storage, in which emissions from fossil fuel projects can be trapped and pumped underground.

- Coal plants that still emit plenty of carbon dioxide, but less than

the generators built decades ago. They are now marketed as high

efficiency, low emissions plants - HELE for short.

Despite billions in research dollars being made available, carbon capture and storage has yielded only two commercial-scale projects - in Canada’s Saskatchewan province and Texas. Both are small, were expensive to build and catch only a fraction of total emissions.

HELE plants have a more significant track-record. They operate at higher temperatures than older models and emit about 10% less. The next generation of HELE plants is known as ultra-supercritical coal plants and emissions are 23% lower, but they are 40 % more expensive to build.

While it’s true that new generation “clean coal” plants are being

built elsewhere, it is not a straightforward story of bold investment.

The overwhelming majority are in China, where they make up nearly 20% of

its huge coal fleet (and the fleet is massive – 20 times the capacity

of Australia’s national grid). China’s extraordinary growth as it

developed this century spurred unprecedented spending on all energy

technologies, but its coal consumption has

been in decline for three years.

The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis found the

Asian giant’s coal plants last year ran at only 47.5% of their capacity,

and estimated it could have US$200bn in stranded coal assets.

Japan

faced a unique challenge after the 2011 Fukushima disaster. It

abandoned nuclear generation and backed new coal to help fill the gap.

But while it has been reported the country is building more than 40

high-efficiency, low-emissions plants, the

Global Coal Plant Tracker database suggests this is an inflated figure. At time of writing,

it lists

12 coal plants as under construction, some of them small by Australian

standards. Only five are listed as HELE; others are the sort of old,

dirty technology plants that no one has argued should be built here. A

further 28 are listed as being assessed or in early planning. Four

proposed plants with a promised capacity of 2.3 gigawatts have been

cancelled this year.

Germany is a more straightforward case. It approved some coal plants

about a decade ago during a European drive to replace dirty old stations

with newer models, and some of them took years to build, but no new

coal proposal has been given a permit since 2009. Depending on the day,

about 40% of the country’s electricity is renewably generated.

The Minerals Council

released a report

in July making the case that HELE coal is the cheapest form of new

electricity plant available, but its findings differed markedly from

other experts who have looked at the issue – not least Finkel’s

government-commissioned review into the electricity grid security.

Critics say it was based on some brave assumptions: that new coal would

not face additional construction and legal costs, that government would

underwrite the risk of future carbon pricing, and that wind and solar

owners would have to pay to have two to three days backup on hand.

It was a far cry from February, when the treasurer brandished a piece of coal in parliament

The business community wasn’t persuaded. (One energy industry leader

summarised: “We don’t understand what they are trying to do.”)

Increasingly, it seems, nor are key members of Malcolm’s Turnbull

cabinet. In a

speech to the Australian Industry Group

in Adelaide, the treasurer, Scott Morrison, spelt out the scepticism.

He stressed the Coalition’s “resource and technology-agnostic” energy

policy and said the government would welcome investment in HELE coal

plants but added: “Let’s also be real about it.”

“These new HELE plans would produce energy at an estimated two and a

half times the cost of our existing coal-fired power stations,” Morrison

said. “They would also take up to around seven years to set up. While

welcome where the economics and engineering stack up, we shouldn’t kid

ourselves a new HELE plant would bring down electricity prices anytime

soon.”

It was a far cry from February, when the treasurer

brandished a piece of coal in parliament,

and it puts him at odds with Tony Abbott and other backbench MPs who

argue the government should use taxpayers’ money to back new coal. But

it was in step with messages from Turnbull, who said

decisions on whether to build coal plants were best left to the market, and the energy minister, Josh Frydenberg, who has

stressed that the government was not planning to build a coal plant itself.

The second half of the parliamentary year is likely to be dominated –

again – by energy and climate policy. It will be fraught within the

government, and predictions about where it will land are courageous.

Options being considered include pairing a clean energy target with a

second program that could help fund a HELE coal plant if it proved

cheaper than other comparable forms of power, or creatively designing

the clean energy target (and the definition of “clean”) so that it

offers new coal the same incentive as, say, a solar farm.

There is no guarantee coal would succeed under either model. But, the

reasoning goes, giving coal an opportunity to compete might help

navigate a vexed issue through a riven party room.

Morrison’s speech offered little hope that for those wanting new coal

plants. He spelt out a different vision: “When it comes to coal, the

best thing we can do is simply ensure the power stations we currently

have – Liddell, Bayswater etc – stay open, remain economic and work

longer into the future. We need to sweat these existing coal-fired

assets for longer.

|

| Steam billows from the cooling towers of the Yallourn coal-fired power station. Photograph: Bloomberg via Getty Images

|

“Not only does this provide critical baseload for our economy in the

decades to come, but it also buys important time as other energy

technologies are developed and can be evolved to match the stability of

more traditional power sources.”

The

reference to Liddell should be telling. When Sydney was pushed to the

edge of blackout during a heatwave in February, it was operating at just

50% capacity owing to ongoing

equipment problems.

A few weeks later, Abbott made a spirited 11th–hour call for Victoria to step in to keep Hazelwood going despite the plant

facing WorkSafe notices for failures that would have cost $400m to fix.

He was widely mocked given the generator’s decrepit state but he wasn’t

without support. If the government does head down this path – propping

up creaking old coal plants because it is not yet convinced by renewable

energy – it might want to brush up on the case of Muja AB.

Links