Yes, Houston, you do have a problem, and – as insensitive as it seems to bring it up just now – some of it is your own making.

Let's be clear upfront. I unreservedly wish that all of your millions of citizens get safely through Tropical Storm Harvey, and the biblical-scale deluge and floods that are forecast to swamp your city in coming days.

Harvey: Catastophic flooding continues

Houston is facing worsening historic flooding in the coming days as Tropical Storm Harvey dumps rain on the city, swelling rivers to record levels.

Houston and its surrounds are home to some 5000 energy-related firms, 17 of which are counted among the Fortune 500 list of largest US companies.

The nearby Gulf Coast is also one of the biggest oil-refining centres anywhere. Not for nothing, the local football team was named the Houston Oilers before it up-rigged elsewhere to become the Tennessee Titans.

One thing that hasn't changed for almost 200 years is scientists' basic understanding humans could alter the chemistry of the atmosphere. By releasing more carbon dioxide, methane (also known as natural gas), and other greenhouse gases, the atmosphere would trap more heat and alter our climate in the process.

The links between fossil fuels and climate change – clear to all but a handful of (often industry-funded) scientists – were hardly promotional talking points oil firms have been keen to trumpet.

In fact, as an important research paper by Harvard University researchers Geoffrey Supran and Naomi Oreskes released last week showed, the largest of them – ExxonMobil – deliberately told the public a story at odds with their own research.

|

Although ExxonMobil is headquartered in another Texan city, Dallas, it bases many operations in Houston. The company has picked Houston to host a sprawling new campus north of the city that will reportedly house 8000 employees.

|

| Hurricane Harvey as it crossed the Gulf coast on Saturday. Photo: NOAA |

|

| IMAGE |

Climate connection

Those seeking to discourage debate about Harvey's climate boost will argue there hasn't been a major (category three or stronger) hurricane crossing the continental US coast in almost 12 years.

|

| Houses were left inundated in Rockport, Texas, with heavy rain still falling in the region. Photo: Alex Scott |

The western Pacific is one basin where scientists are increasingly confident of a discernable trend that is not good news for the large populations in China, Japan and the Philippines – among others – that are exposed. One study last year found as much as a four-fold increase in the number of super typhoons.

|

| A photo taken from the International Space Station shows Hurricane Harvey over Texas on Saturday. Photo: Jack Fischer/NASA via AP |

These include a study last year that found the probability of an extreme rainfall event in the central US Gulf Coast had increased 1.4 times because of anthropogenic climate change.

A separate study in 2013 examined, among others, the contribution of climate change to super storm Sandy, which left a damage bill of $US60 billion ($75 billion) across the north-eastern US in 2012.

"Our future scenarios of Sandy-level return intervals are concerning, as they imply that events of less and less severity (from less powerful storms) will produce similar impacts," the paper found. "Further aggravating, the frequency and intensity of major storms/surges are likely to increase in a warming climate."

Impacts made worse

Andrew King, a climate extremes research fellow at the University of Melbourne and the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science, said the complexity of cyclones makes it difficult to attribute climate change to events such as Hurricane Harvey.

"These are hard to simulate, extreme cyclones, on the grid scale of climate models," he says.

What is clearer, though, is a warming atmosphere makes heavy rainfall events more possible. Each degree increase allows the atmosphere to hold roughly 7 per cent more moisture.

Similarly, rising sea levels means any storm surge accompanying a cyclone will be worse. "Even a small increase in sea levels creates a big increase of the extent of a storm surge going inland," King said.

Sea levels are rising globally – at about 3.4 millimetres a year – as glaciers and land-based ice sheets melt, and warming oceans expand.

Michael Mann, a prominent US climate scientist based at Pennsylvania State University, noted in a Facebook post how unusually warm Gulf waters, provided the energy for Harvey's near-record rate of intensification as it neared the coast.

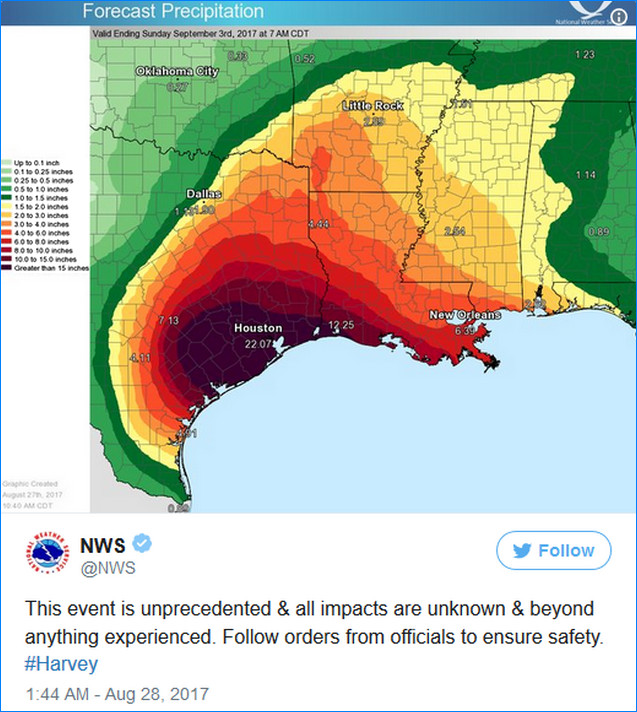

Mann also points to the unusually stationary nature of the hurricane, which is leading to a "seemingly endless deluge" that could dump as much as 1.3 metres of rainfall before it's done.

|

| IMAGE |

When the clean-up eventually begins in Houston and other regions battered and drenched in this week's tempest, questions about what protection will be needed for the next big storm will no doubt surface.

Given its unusual dependence on fossil-fuel industries, though, it will be interesting to watch if Houston queries – tactfully and delicately – its own contribution to the catastrophe.

|

| IMAGE |

- Is Hurricane Harvey A Harbinger For Houston’s Future?

- It's A Fact: Climate Change Made Hurricane Harvey More Deadly

- What we know so far about tropical storm Harvey

- Did Climate Change Intensify Hurricane Harvey?

- Climate change did not “cause” Harvey, but it’s a huge part of the story

- Was Climate Change Involved in Making Hurricane Harvey?