New York Times - Somini Sengupta

It’s hot. But it may not be the new normal yet. Temperatures are still rising.

|

| Residents of New Delhi in June. Extreme heat hits poor and already-hot regions like South Asia especially hard. Credit Saumya Khandelwal for The New York Times |

This summer of fire and swelter looks a lot like the future

that scientists have been warning about in the era of climate change,

and it’s revealing in real time how unprepared much of the world remains

for life on a hotter planet.

The

disruptions to everyday life have been far-reaching and devastating. In

California, firefighters are racing to control what has become the

largest fire in state history. Harvests of staple grains like wheat and

corn are expected to dip this year, in some cases sharply, in countries

as different as Sweden and El Salvador. In Europe, nuclear power plants

have had to shut down because the river water that cools the reactors

was too warm. Heat waves on four continents have brought electricity

grids crashing.

And dozens of heat-related deaths in Japan this summer offered a foretaste of what researchers warn could be big increases in mortality from extreme heat. A

study last month in the journal PLOS Medicine

projected a fivefold rise for the United States by 2080. The outlook

for less wealthy countries is worse; for the Philippines, researchers

forecast 12 times more deaths.

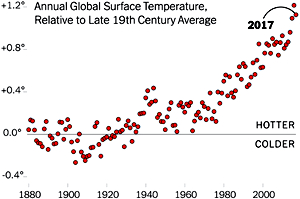

Globally, this is shaping up to be the fourth-hottest year on record. The only years hotter were the

three previous ones. That string of records is part of an accelerating climb in temperatures since the start of the industrial age that scientists say is clear evidence of climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions.

And even if

there are variations in weather patterns in the coming years, with some

cooler years mixed in, the trend line is clear:

17 of the 18 warmest years since modern record-keeping began have occurred since 2001.

“It’s

not a wake-up call anymore,” Cynthia Rosenzweig, who runs the climate

impacts group at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, said of

global warming and its human toll. “It’s now absolutely happening to

millions of people around the world.”

Be careful before you call it the new normal, though.

Temperatures

are still rising, and, so far, efforts to tame the heat have failed.

Heat waves are bound to get more intense and more frequent as emissions

rise, scientists have concluded. On the horizon is a future of cascading

system failures threatening basic necessities like food supply and

electricity.

For many scientists, this is the year they started living climate change rather than just studying it.

“What we’re

seeing today is making me, frankly, calibrate not only what my children

will be living but what I will be living, what I am currently living,”

said

Kim Cobb,

a professor of earth and atmospheric science at the Georgia Institute

of Technology in Atlanta. “We haven’t caught up to it. I haven’t caught

up to it, personally.”

This week, she

is installing sensors to measure sea level rise on the Georgia coast to

help government officials manage disaster response.

Katherine Mach, a Stanford University climate scientist, said something had shifted for her, too.

“Decades

ago when the science on the climate issue was first accumulating, the

impacts could be seen as an issue for others, future generations or

perhaps communities already struggling,” she said, adding that science

had become increasingly able to link specific weather events to climate

change.

“In our increasingly muggy

and smoky discomfort, it’s now rote science to pinpoint how

heat-trapping gases have cranked up the risks,” she said. “It’s a shift

we all are living together.”

|

| A shrunken section of the Rhine near Düsseldorf, Germany, in August. Credit Lukas Schulze/Getty Images |

|

| A swimming pool in Yongin, South Korea, in August. Credit Chung Sung-Jun/Getty Images |

|

| Central Tokyo in July. A heat wave killed dozens across Japan this summer. Credit Koji Sasahara/Associated Press |

Globally, the hottest year on record was 2016. That was not totally

unexpected because that year there was an El Niño, the Pacific climate

cycle that typically amplifies heat.

More surprising, 2017, which was not an El Niño year,

was almost as hot.

It was the third-warmest year on record, according to the National

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or the second-warmest, according

to NASA.

The

first half of 2018, also not marked by El Niño, was the fourth-warmest on record, NOAA found.

In the lower 48 United States, the period between

May and July ranked as the hottest ever,

according to NOAA, with an average temperature of 70.9 degrees

Fahrenheit (21.6 degrees Celsius) which was 3.4 degrees Fahrenheit (1.9

Celsius) above average in the period since record-keeping began in 1895.

Sea levels continued their upward trajectory last year, too, rising

about 3 inches, or 7.7 centimeters, higher than levels in 1993.

What does all that add up to?

For

Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California Los

Angeles, it vindicates the scientific community’s mathematical models.

It doesn’t exactly bring comfort, though.

“We

are living in a world that is not just warmer than it used to be. We

haven’t reached a new normal,” Dr. Swain cautioned. “This isn’t a

plateau.”

Against that background, industrial emissions of carbon dioxide

grew to record levels in 2017, after holding steady the previous three years.

Carbon in the atmosphere was found to be at the highest levels in 800,000 years.

Despite a global agreement in Paris two years ago to curb greenhouse gas

emissions, many of the world’s biggest polluters — including the United

States, the only country in the world

pulling out of the accord — are

not on track to meet the reductions targets

they set for themselves. Nor have the world’s rich countries ponied up

money, as promised under the Paris accord, to help the poor countries

cope with the calamities of climate change.

|

| Houses destroyed by the Carr Fire in Redding, Calif., last month. Credit Noah Berger/Associated Press |

|

| A woman who fled her home in Lakeport, Calif., as the River Fire approached in July. Credit Noah Berger/Associated Press |

Still,

scientists point out that with significant reductions in greenhouse gas

emissions and changes to the way we live — things like

reducing food waste, for example — warming can be slowed enough to avoid the worst consequences of climate change.

Some governments, national and local, are taking action. In an effort to avert heat-related deaths, officials are promising to

plant more trees in Melbourne, Australia, and covering roofs with

reflective white paint in Ahmedabad, India. Agronomists are trying to develop seeds that have a better shot at surviving heat and drought.

Switzerland hopes to prevent railway tracks from buckling under extreme heat by painting the rails white.

Climate

scientists are also trying to respond faster, better. Dr. Rosenzweig’s

team at NASA is trying to predict how long a heat wave might last, not

just how likely it is to occur, in order to help city leaders prepare.

Similar efforts to forecast the distribution of extreme rainfall are

aimed at helping farmers.

Researchers with World Weather Attribution are working to refine their models to make them more accurate. “In Europe the warming is faster than in the models,” said

Friederike Otto, an associate professor at Oxford University who is part of the attribution group.

Her group recently concluded that a human-altered climate had

more than doubled the likelihood of the record-high temperatures in northern Europe this summer.

The impact of those

records is being felt in multiple ways. The continent’s

power supply is overstretched as air-conditioners are cranked up.

Then, there’s the impact of heat and drought on farms. In El Salvador, a

country reeling from gang violence, farmers in the east of the country

stared at a failed corn harvest this summer as temperatures soared to a

record 107 degrees Fahrenheit, or about 41 degrees Celsius. The skies

were rainless for up to 40 days in some places, according to the

government.

|

| A farmer in Usulután, El Salvador, with parched corn. Temperatures in the area have hit 107 degrees Fahrenheit this summer. Credit Oscar Rivera/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images |

Wheat production in many countries of the European Union is set to decline this year. In Britain,

wheat yields are projected to hit a five-year low. German farmers say their

grain harvests are likely to be lower than normal. And in Sweden, record-high temperatures have left fields parched and farmers scrambling to find fodder for their livestock.

Palle

Borgstrom, president of the Federation of Swedish Farmers, said in an

interview that his group estimated at least $1 billion in agricultural

sector losses.

“We get quite a few

phone calls from farmers who are lying awake at night and worrying about

the situation,” he said. “This is an extreme situation that we haven’t

seen before.”

Links