|

New South Wales, which was 100% drought-declared in August 2018, is already suffering climate impacts.

Michael Cleary

|

While Australia still lacks effective climate change policies, the debate has definitely shifted. It’s particularly noticeable to scientists, like myself, who were very active participants in the Australian climate debate just a few years ago.

The debate has moved away from the basic science, and on to the economic and political ramifications. And if advocates for reducing greenhouse emissions don’t fully recognise this, they risk shooting themselves in the foot.

|

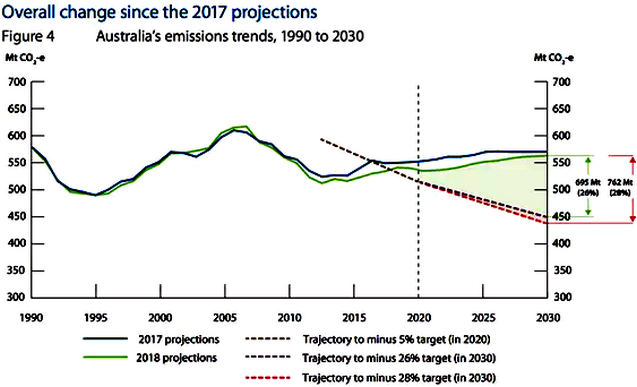

| Australia’s carbon dioxide emissions are not falling. Department of Environment and Energy |

Old-school climate change denial, be it denial that warming is taking place or that humans are responsible for that warming, featured prominently in Australian politics a decade ago. In 2009 Tony Abbott, then a Liberal frontbencher jockeying for the party leadership, told ABC’s 7.30 Report:

I am, as you know, hugely unconvinced by the so-called settled science on climate change.The theory and evidence base for human-induced climate change is vast and growing. In contrast, the counterarguments were so sloppy that there were many targets for scientists to shoot at.

Climate “sceptics” have always been very keen on cherrypicking data. They would make a big fuss about some unusually cold days, or alleged discrepancies at a handful of weather stations, while ignoring broader trends. They made claims of data manipulation that, if true, would entail a global conspiracy, despite the availability of code and data.

Incorrect predictions of imminent global cooling were made on the basis of rudimentary analyses rather than sophisticated models. Cycles were invoked, in a manner reminiscent of epicycles and stock market “chartism” – but doodling with spreadsheets cannot defeat carbon dioxide.

That was the state of climate “scepticism” a decade ago, and frankly that’s where it remains in 2019. It’s old, tired, and increasingly irrelevant as the impact of climate change becomes clearer.

Australians just cannot ignore the extended bushfire season, drought, and bleached coral reefs.zzz

“Since 2010, all of Western Australia’s reefs systems have bleached at least once” due to anthropogenic heating.— Terry Hughes (@ProfTerryHughes) May 22, 2019

ALL of Australia’s reefs are rapidly declining. https://t.co/icJgojEyAV https://t.co/eNvVAq84tR https://t.co/8R0S5BxsjA

Partisans

Climate “scepticism” was always underpinned by politics rather than science, and that’s clearer now than it was a decade ago.

Several Australian climate contrarians describe themselves as libertarians - falling to the right of mainstream Australian politics. David Archibald is a climate sceptic, but is now better known as candidate for the Australian Liberty Alliance, One Nation and (finally) Fraser Anning’s Conservative National Party. The climate change denying Galileo Movement’s claim to be to be non-partisan was always suspect - and now doubly so with its former project leader, Malcolm Roberts, representing One Nation in the Senate.

Given this, it isn’t surprising that relatively few Australians reject the science of climate change. Just 11% of Australians believe recent global warming is natural, and only 4% believe “there’s no such thing as climate change”.

Old-school climate change denial isn’t just unfounded, it’s also unpopular. Before last month’s federal election, Abbott bet a cafe patron in his electorate A$100 that “the climate will not change in ten years”. It reminded me of similar bets made and lost over the past decade. We don’t know whether Abbott will end up paying out on the bet – but we do know he lost his seat.

This is the signed $100 bet former Australian prime minister Tony Abbott made with a woman at a Manly coffee shop, "that the climate will not change in ten (10) years". Read her story: https://t.co/CUIBP0VTvc #WarringahVotes #auspol #ausvotes2019 #ausvotes #ausvotes19 pic.twitter.com/hkJsRmdLdg— Guardian Australia (@GuardianAus) May 7, 2019

The shift

So what has changed in the years since Abbott was able to gain traction, rather than opprobrium, by disdaining climate science? The Australian still runs Ian Plimer and Maurice Newman on its opinion pages, and Sky News “after dark” often features climate cranks. But prominent politicians rarely repeat their nonsense any more. When the government spins Australia’s rising emissions, it does it by claiming that investing in natural gas helps cut emissions elsewhere, rather than by pretending CO₂ is merely “plant food”.

As a scientist, I rarely feel the need to debunk the claims of old-school climate cranks. OK, I did recently discuss the weather predictions of a “corporate astrologer” with Media Watch, but that was just bizarre rather than urgent.

Back in the real world, the debate has shifted to costs and jobs.

Modelling by the economist Brian Fisher, who concluded that climate policies would be very expensive, featured prominently in the election campaign. Federal energy minister Angus Taylor, now also responsible for reducing emissions, used the figures to attack the Labor Party, despite expert warnings that the modelling used “absurd cost assumptions”.

Shorten is still refusing to costs his climate policies. BAEconomics has told us. 336,000 jobs lost, a $9,000 hit to annual wages and a 58% increase in electricity. No wonder Shorten won’t ‘fess up. #auspol https://t.co/3S7UB4OT6v— Angus Taylor MP (@AngusTaylorMP) April 30, 2019

Many people still assume the costs of climate change are in the future, despite us increasingly seeing the impacts now. While scientists work to quantify the environmental damage, arguments about the costs and benefits of climate policy are the domain of economists.

Jobs associated with coal mining were a prominent theme of the election campaign, and may have been decisive in Queensland’s huge anti-Labor swing. It is obvious that burning more coal makes more CO₂, but that fact doesn’t stop people wanting jobs. The new green economy is uncharted territory for many workers with skills and experience in mining.

That said, there are economic arguments against new coalmines and new mines may not deliver the number of jobs promised. Australian power companies, unlike government backbenchers and Clive Palmer, have little enthusiasm for new coal-fired power stations. But the fact remains that these economic issues are largely outside the domain of scientists.

Debates about climate policy remain heated, despite the scientific basics being widely accepted. Concerns about economic costs and jobs must be addressed, even if those concerns are built on flawed assumptions and promises that may be not kept. We also cannot forget that climate change is already here, impacting agriculture in particular.

Science should inform and underpin arguments, but economics and politics are now the principal battlegrounds in the Australian climate debate.

Links

- Australia's greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise

- Climate sceptic or climate denier? It’s not that simple and here’s why

- Whichever way you spin it, Australia’s greenhouse emissions have been climbing since 2015

- More than half of the corals died on red reefs, in two consecutive summers with record-breaking heat

- Mega mine next to Adani quietly put on hold, thousands of promised jobs in doubt

- Facebook’s Newest ‘Fact Checkers’ Are Koch-Funded Climate Deniers

- The Next Reckoning: Capitalism And Climate Change

- Climate Change Denial Is Evil, Says Mary Robinson

- Donald Trump’s Climate Denial Gets More Ridiculous By The Day

- Malcolm Farr: ‘The Public Debate On The Existence Of Climate Change Is Over And We Are Owed An Apology’

- How The Weather Gets Weaponized In Climate Change Messaging

- 11 Things Climate Change 'Dismissive' People Say On Social Media

- This Summer Is Angry: Are You?

- Using The Big Freeze To Deny Climate Change... Stupidity Or Cynicism?