|

| Scientists say sea levels in Tasmania are rising by 3mm a year. (Facebook: Discover Tasmania) |

Key points:

|

Scientists and international organisations have been issuing the climate change warnings for decades, saying the future of Earth as we know it is under threat.

Tasmania — renowned for its natural beauty — is not immune, suffering its fair share of natural disasters and slowly-eroding land, all attributed — at least in part — to the changing climate. But if we know a bit of how bad it is going to be, do we know how bad it already is?

The ABC investigated how much the island state's climate has changed in the past 100 years.

|

| Usually wet rainforest wilderness areas have been scorched in the past few years. (Instagram: Fire Rescue Tasmania) |

Climate change 'unparalleled' on global scale  |

| Scientists find global warming is being felt (almost) everywhere at the same time and the warming is unprecedented over the past 2,000 years. |

"It doesn't matter how you cut it up, you still get the same message that temperatures over Tasmania have risen over the last century, particularly since the 1950s," he said."It's such a clear-cut story."

Averaged over the entire state, Mr Barnes-Keoghan said Tasmania is now about a degree warmer than it was a century ago.

But hot temperatures are also now more extreme than they used to be, with fewer very cold days.

"We're not saying that the temperature everyday is now a degree warmer than it was, but the average has moved up and we're seeing more of those extremely high temperatures, so your 35 and 40-degree days," Mr Barnes-Keoghan said.

|

| Ian Barnes-Keoghan says a graph showing average temperatures shows the general increase of about a degree over the past 100 years, and especially since the 1950s. (Supplied: Bureau of Meteorology) |

"Since 1910, there's been 12 days where somewhere in Tasmania has reported a temperature of 40 degrees or more. Four of those occurred in the first 93 years, the other eight only occurred in the last 17, and two of those were this year.""It's often those extremes that people really notice."

As for the argument that the warming of the climate is cyclical, Mr Barnes-Keoghan said there was no reason why people should expect average temperatures will cool down again.

In fact, Scientists writing in the journal Nature this week said there was no evidence for "globally coherent warm and cold periods" over the past 2,000 years prior to industrialisation.

"We have a very good understanding of the mechanisms behind this warming, so the significant cause has been an increase in the concentration of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere," Mr Barnes-Keoghan said.

"So just by simple physics that leads to an increase in the average temperature because more warmth is trapped close to the surface."

|

| Tasmania is known for its freezing temperatures. (Supplied: Pat Fasnacht) |

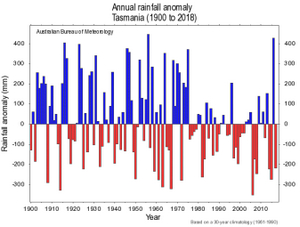

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it is now also drier in Tasmania, with average rainfall across the state decreasing.

|

| Ian Barnes-Keoghan says since the 1970s there have been fewer "wet" years, but 2016 was the second wettest on record. (Supplied: Bureau of Meteorology ) |

"One is that we still get wet years, like it rained a lot in 2016 — but the wet years have become less common and the dry years have become more common," he said.

He said the decline is strongest in late Autumn, heading into early winter.

Mr Barnes-Keoghan explained rainfall now behaves differently than it did in the past.

"[In the past,] you'd get a couple of dry years, then a couple of wet years to make up for it," he said.

"But sometime around the mid-70s, that pattern seems to have changed.

"Instead of having a mixture, it went to getting several dry years in a row, then a wettish year but not really that exciting, then a couple of dry years and just not getting those recharge years."But explaining why is a bit more complex.

"Rainfall is complicated, but one of the reasons there's been less rainfall is there are less rain-bearing systems," Mr Barnes-Keoghan said.

"That partly comes about because of an increase in high-pressure systems — that's a known and expected consequence of increasing greenhouse gases.

"Rainfall is hugely variable from year to year, much more variable than temperature, so picking out trends in rainfall is much harder."

Mr Barnes-Keoghan also said the warmer atmosphere holds more moisture, so when it does rain, it's now often in quicker and heavier bursts.

But what about wind and snow?

|

| No data is kept on snowfall but many believe it's not as prevalent as in the past. (Supplied: Cam Blake Photography) |

Mr Barnes-Keoghan said while it certainly seemed that way, there was no available data to back that up.

|

| Ian Barnes-Keoghan says average temperatures are not expected to cool down again. (ABC Radio Hobart: Carol Rääbus) |

That's because it doesn't snow that often over most of Tasmania and in particular, it doesn't snow that often in populated areas.

Mr Barnes-Keoghan said a lot of the historical observations really relied on somebody being there to take the measurement, which didn't always happen.

"I've been here for a long time and I get the impression that snow is less common than it was, but that's completely an anecdote," he said.

Wind is also hard to measure, though Mr Barnes-Keoghan said average windspeeds were decreasing, albeit not by much.

He said the bureau had only really collected data on wind since the 1990s, and even then, it might be skewed because equipment had been positioned in locations known to be particularly windy.

"To measure rainfall you basically need a jam jar, I mean we have very sophisticated jam jars which are calibrated, but measuring wind speed is really difficult," he said.

"The instruments we've got now were really only developed during the 1950s and only became widespread in Australia during the 80s and 90s. [They] only became really important around the 90s so we've really only got measurements since then."Is Tasmania going under (the sea)?

Not quite yet, but sea levels are estimated to be rising 3 millimetres each year.

Retired oceanographer and sea-level-rise expert John Hunter said sea levels had risen by about 16 centimetres since 1841 — when the first sea-level benchmark was put in place at Port Arthur, on Tasmania's south-east coast, adding levels had risen by about the same amount "pretty much everywhere".

|

| John Hunter kneels next to the 1841 sea level gauge which is carved into rock at Port Arthur. (Supplied: Frederique Olivier) |

Mr Hunter said that while 3 millimetres a year might not sound like much, it had big consequences.

"The rule of thumb I use is that if you have about 10 centimetres of sea-level rise, which we've already seen last century, [the] frequency of flooding events goes up by a factor of three. So 10 centimetres trebles the amount of flooding events."He said people tended not to notice the changes because they occurred over decades and coastal infrastructure was built accordingly, so "people just build sea walls a bit higher".

But people may see shorelines receding, which is one of the results of rising seas.

"For every metre of sea-level rise, you lose between 100 and 200 metres of shoreline," he said.

|

| Wet years such as 2016, which saw heavy flooding, are becoming less common, according to the Bureau of Meteorology. (Copyright Neil Hargreaves) |

NOTE: The ABC investigated changes in the island state's climate as part of our Curious Climate series. Curious Climate Tasmania is a public-powered science project, bridging the gap between experts and audiences with credible, relevant information about climate change. The project is a collaboration between ABC Hobart, UTAS Centre for Marine Socioecology, the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS), the Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture (TIA), and the CSIRO.

Links

- 'Is 2 degrees warmer really that bad?': Scientists answer your questions

- 'We're seeing metres lost': This is what climate change looks like

- No, we haven't experienced anything like this global warming in the past 2,000 years

- I debunked undying climate change myths so you don't have to

- Europe hit by heatwave and hailstorms, experts warn Greenland ice could melt

- Three hours to impact: Tsunami modelling shows how Queensland’s coast would cope