|

| Peter Holding is a mixed farmer from Harden, NSW, and member of Farmers for Climate Action. (ABC News: Anna Vidot) |

Key Points

|

Climate change has already cost farmers more than $1 billion since 2000, according to ABARES.

Third-generation lamb and cropping farmer Peter Holding said government inaction on global warming could have disastrous flow-on effects to the agriculture industry.

"Climate change poses a cataclysmic set of challenges for farmers," the Farmers for Climate Action member said.

"It's pretty severe and it's getting worse."As the frequency [of natural disasters] increases, the insurance premiums are just going to go up — there's no doubt about that."

The southern New South Wales farmer and volunteer firefighter said prolonged fire seasons are just one example of how climate change is affecting agricultural practices.

"The Canberra fires in 2003 was when we first saw the phenomenal firestorm effect," he said.

"And that's getting more common."

|

| Fire surrounds a homestead during the Canberra fires in January 17, 2003. (Copyright: Jeff Cutting) |

Rising risks, rising costs

Insurance Council of Australia spokesman Campbell Fuller said the industry was worried about the effects of man-made climate change.

"The insurance industry is very aware of concerns in the rural sector about climate change, natural disasters and about access to insurance," he said.

"Insurers gather the latest available data from governments, especially around bushfire exposure and flood exposure, as well as seasonal forecasts from the Bureau of Meteorology."

Mr Fuller says insurers build a robust picture of the seasonal exposure that properties have per annum, which is then is priced into premiums.

"As the climate changes, and as risks are reassessed, that logically leads to changes in premiums to reflect the risks," he said.

|

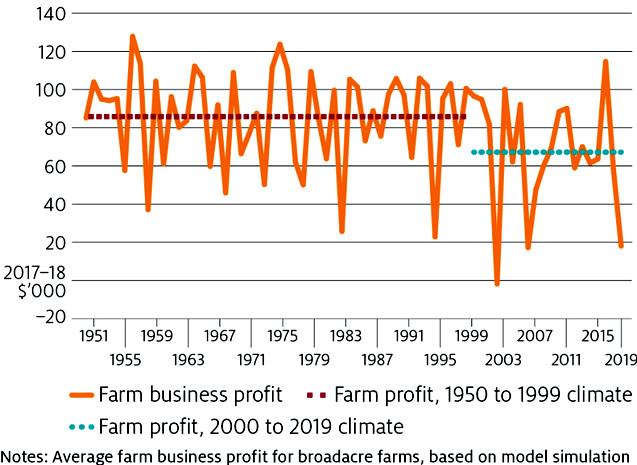

| Effect of climate variability on average farm profits 1949-50 to 2018-19 at current farms and commodity prices.(Supplied: ABARES) |

Mr Fuller said appropriate land use and resilient infrastructure in areas of higher risk to natural disasters needed to be prioritised.

"Changes in risk that can be predicted by climate change modelling need to be taken into account," he said.

"In many parts of Australia there's plenty of evidence that primary producers are taking measures to reduce the risks to their properties into their own hands."

Eighty per cent of Australian households are underinsured, and Mr Fuller says that percentage is probably much higher in rural areas.

|

| This banana plantation at Taylors Arm, west of Macksville, was destroyed by fire in 2019. (ABC Rural: Claire Wheaton) |

"When properties are not insured, communities can struggle to rebuild after natural disasters and the burden falls more heavily on charities and government in the recovery phase."

Mr Fuller said farmers were likely to insure infrastructure such as their homes, sheds and equipment, but fences, livestock and crops were less likely to be included.

"There is no real silver bullet here," he said.

"It's a combination of actions that need to take place at a community level, and involving all levels of government."Mr Holding said the cost of premiums meant insurance was not an option for some producers.

"I've had to pull back the farm's scale an awful lot to cut debt and make sure that we're still viable," he said.

|

| Valuable farm machinery was destroyed by fire on the Duff beef and soybean property in the Upper Macleay Valley in 2019. (Supplied: Carolyn Duff) |

Financial strain is not the only issue climate change has delivered to farmers.

"Unfortunately we're getting less good years and a lot more variability," Mr Holding said.

"There's a lot of impacts and I can't see it stopping any time soon.

"The droughts are just continuing, since the turn of the century we've had [so many years] of drought, interlaced with floods."

|

| This map shows the decline of winter rainfall across southern Australia over the past 20 years. (Supplied: CSIRO/BOM) |

"Cutting emissions is the only option there, and that means moving away from fossil fuels — but the government seems wedded to that," he said.

"The fossil fuel industry is creating emissions and that is slowly but surely making agriculture unviable."We've cut the emissions from livestock probably in half, farmers in cropping areas have done all sorts of things to reduce the use of diesel and better use fertilisers.

"So farmers are working on all of these problems to cut their own emissions, but we definitely need some quick action to reduce the emissions of fossil fuel."

Links

- (AU) Climate Change Has Cut Australian Farm Profits By 22% A Year Over Past 20 Years, Report Says

- (AU) Climate Change Slashes More Than $1 Billion From Farm Production Value Over Past 20 Years: ABARES

- Fear Of Drought, Flood And Fires Leads Farmers To Plea For Urgent Action On Climate Change

- Insurers Urge Morrison To Take On Climate Action

- Climate Change Predicted To Wipe $571 Billion Off Property Values

- Australian Insurer QBE To Exit Thermal Coal Over Climate Change

- Climate Change Could Make Insurance Too Expensive For Most People – Report

- Australian Insurers Say 'Act Now' On Climate Change

- From shiraz to Wagyu, fires and floods have ruined Australia's fresh food image. So what happens now?

- Are farmers getting climate change support?