As warnings arise that Australia is becoming “globally isolated”, one expert says the PM has a plan, despite his combative nature towards the issue.

Scott Morrison is “bumping the government forward increment by

increment” on the issue of climate change as the Prime Minister faces heat

from international leaders to step up Australia’s action on the issue.

On Monday, Mr Morrison defended his government’s actions on climate change in a debate with Labor leader Anthony Albanese, saying he will stand firm on climate policies despite Australia’s emissions increasing year-on-year.

It comes as US President-elect Joe Biden signals he will demand more from America’s allies — including Australia — despite what has been a difficult issue for Morrison’s Liberal party and which threatens to leave Australia “globally isolated”.

The President-elect has pledged to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 and have zero emissions from the electricity sector by 2035.

|

| The Prime Minister Scott Morrison wears a face mask in Parliament House, Canberra. Picture: Gary Ramage Source: News Corp Australia |

It comes as a former US government official, Kim Hoggard, warned Biden’s presidency will add more pressure on Scott Morrison to create positive climate change policies.

“That will put some pressure on the Australian government to respond maybe on carbon emission targets and it’s an opportunity for the Australian government to rethink it’s position around that,” Hoggard, who worked under the Ronald Reagan and George W Bush administrations, told 2GB.

Former Liberal Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull was famously dumped from the Liberal party and later said it was “influenced by a group that is denialist and reactionary on climate change”, according to The Australian.

In an interview with The Guardian, Mr Turnbull said the party had struggled on the issue from as far back as 2007.

|

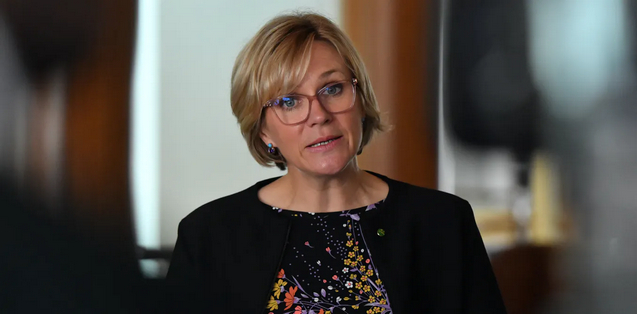

| The Leader of the Australian Labor Party, Anthony Albanese met with bushfire survivors demanding action on climate change last month. Picture: Gary Ramage Source: News Corp Australia |

Last week, it was revealed a group of international leaders, led by Britain and France, penned a letter to the PM on October 22 to make new commitments to the climate crisis, calling on countries to rebuild “in a way that charts a greener, more resilient, sustainable path”.

Accused of “leaving Australia behind” by Mr Albanese on Monday, Mr Morrison resisted pressure to set more ambitious climate goals but said he would work with Mr Biden on issues including climate change.

“Australia’s policies will be set in Australia and nowhere else for Australia’s purposes,” the PM said.

The Prime Minister said his government had a plan to achieve emissions reductions under the Paris Agreement yet he warned other countries would not influence the federal government.

“We would be welcoming the United States back into the Paris Agreement, somewhere we have always been,” Mr Morrison said.

“We met and beat our Kyoto targets, and we believe we will do the same when it comes to our Paris commitments as well.

“Australia will always set its policies based on Australia’s national interests and the contributions that we are making in these areas.”

Will Australia join @JoeBiden and embrace net zero emissions by 2050? "Australia will always set its policies based on Australia's national interests" @ScottMorrisonMP "The United States will make their decisions... and we'll do the same" #auspol @SBSNews pic.twitter.com/RS4CAqHpbq

— Brett Mason (@BrettMasonNews) November 8, 2020

For net zero emissions by 2050:

— Anthony Albanese (@AlboMP) November 9, 2020

Every state and territory

Australian Industry Group

Business Council of Australia

National Farmers' Federation

AGL

BHP

Rio Tinto

Santos

Telstra

Origin

Energy Australia

Property Council

Aluminium Council

Commonwealth Bank

Against:

Scott Morrison

Yet according to one expert, it seems the Prime Minister has a plan of action.

The Guardian’s Katharine Murphy told ABC’s The Drum on Monday afternoon that the PM found himself in “difficult territory”, as popular opinion on climate change grows and the pressure heats up. Despite this, he is “bumping the government forward increment by increment on the issue.

The political editor said while he may want to affect change, he is constrained by the inner politics of his own party.

“This is really difficult territory for Scott Morrison,” she said.

“He is trying to step off the abject wrecking of the past but is constrained by forces within his own political organisation.

“If he stood up tomorrow and said, ‘fair cop, we’ll do net zero by 2050’, the National party would go berserk.

“The Coalition has become very adept at weaponising climate change in election contests.”

"He is bumping the government forward, increment by increment, on climate. That is the fairest reading."@murpharoo says US President-elect Biden's commitment to climate change action puts PM Scott Morrison in 'difficult territory' back home. #TheDrum pic.twitter.com/vXEhTP3r8q

— ABC The Drum (@ABCthedrum) November 9, 2020

Mr Albanese accused the government of lacking a climate change policy but Mr Morrison said on Monday Australia would reduce emissions using its “technology road map”.

“It’s not one size fits all in terms of the commitments that are out there. Our goal is to achieve that as soon as you can,” he said.

“But we’ll do it on the basis of the technology road map, and so we have the technology to achieve lower emissions in the future. You’ve got to have the plan to get there.

“The US will make their decisions based on their interests and their capabilities and how their economy is structured and we’ll do the same.

“Our 2030 targets are set and we will meet them.”

Scott Morrison is completely isolated on climate change. Why won't he commit to net zero emissions by 2050? pic.twitter.com/s0b4YB1i8q

— Mark Butler MP (@Mark_Butler_MP) November 9, 2020

Nowhere left to hide, Scott Morrison.

— Adam Bandt (@AdamBandt) November 9, 2020

For year’s Aust has joined Trump to block global climate action.

At next climate summit, countries are asked to lift their 2030 goals.

Will PM take more action over this critical decade?

Or hang out with Saudi Arabia & Russia instead?

In a heated question time, Mr Morrison also blamed the lack of clarity on the question of cost.

“Until such time as we can be very clear with the Australian people about what the cost of that is and how that plan can deliver on that commitment, it would be very deceptive on the Australian people and not honest with them, Mr Speaker, to make such commitments without being able to spell that out to Australians.”

It comes as Warringah independent MP Zali Steggall introduced a climate change bill into parliament with support from her crossbench colleagues trying to get the target enshrined in legislation, saying the coalition was “dragging its feet”.

She called on Scott Morrison to allow a conscience vote of coalition members on her bill but whether or not the bill will be debated remains to be seen.

Links- (Video) US Election 2020: Morrison pledges to work with Biden on climate change

- Like water for electricity, we can go with the flow for cleaner energy

- Australia the outlier in Biden's brave new zero-emissions world

- A Biden Victory Positions America For A 180-Degree Turn On Climate Change

- Net zero: what if Australia misses the moment on climate action?

- A Joe Biden victory could push Scott Morrison – and the world – on climate change

- Scott Morrison refuses to commit to net zero emissions target by 2050

- Joe Biden win will put pressure on Scott Morrison over climate change

- Biden to change US tune on climate, China

- Australian govt will feel the heat when a Biden administration rejoins the Paris climate agreement

- Places across Australia people will soon struggle to live

- Have your say on global warming and what you’re doing

- The biggest climate change myths debunked