|

|

Alan Nichols has had severe health problems since last year's

bushfire season. (ABC News: Billy Cooper) |

A fire was rapidly approaching Malua Bay on the New South Wales South Coast and the thick smoke from the looming firestorm was making it hard to breathe.

"It was all dark, as if it was night-time, smoke everywhere," he said.

"It hurt my eyes just to be outside.

"My lungs were going, sort of solid."

Alongside other fellow holidaymakers, Mr Nichols spent New Year's Eve trapped on the beach watching homes burst into flames.

By the time he made it home to Canberra, a heavy cough had set in — coinciding with the thick smoke haze blanketing much of the east coast of Australia.

"We weren't able to have the cooling going because it was pumping the smoke in," Mr Nichols said.

"There was just no relief."

|

|

Parliament House in heavy haze after Canberra was blanketed in

bushfire smoke. (AAP: Lukas Coch) |

A month after the initial incident, Alan's family urged him to see a doctor.

New figures show he was one of thousands of Australians who struggled with breathing difficulties in the aftermath of the fires.

In the ACT, pharmacy inhaler sales jumped by up to 204 per cent in the week of January 5.

On the South Coast of NSW, prescriptions rose 73 per cent in the second week of January, compared to the same time last year, while in the Hume area of Victoria — an area where the bushfires hit — inhaler sales spiked by 74 per cent.

Cardiologist Arnagretta Hunter said the figures were a clue as to how many Australians suffered health effects from the smoke.

|

|

Dr Hunter said the long-term effects bushfire smoke were still an

unknown. (ABC News) |

Its aim was to fill a massive knowledge gap that exists in the scientific world about the short and long-term impacts of bushfire smoke.

"We know a lot about air pollution, we don't know as much about bushfire smoke," she said.

Preliminary results of a survey of more than 2,000 Canberra residents showed that between December and January, 89 per cent reported experiencing irritated eyes, scratchy throat or cough.

Almost half of the respondents felt anxious and or depressed as a result of the smoke.

While many of their health impacts will resolve, the bigger question is what will happen to these people long term.

The royal commission into bushfires heard the smoke led to an extra 3,320 hospitalisations and 429 deaths across the country.

"They died from chest infections and pneumonia," Dr Hunter said."[And] they've died from heart attack and stroke and cardiovascular disease; they've died because of an increase in the risk of sepsis associated with hazardous air pollution exposure."

Dr Hunter said the health impacts of smoke shouldn't be looked at in isolation, given smoke usually occurs in combination with what public health experts describe as a "silent killer" — heat.

"Thousands more people presented to hospital with cardiovascular problems, stroke problems and with pulmonary problems or exacerbations of asthma and emphysema."

|

|

Mr Nichols was prescribed many drugs to help with his condition.

(ABC News: Billy Cooper) |

After being put on an inhaler at the end of summer he started developing pain in his legs.

He was diagnosed with blood clots and had to be rushed to the emergency department.

"I'll be on blood thinners for life now," he said.

But it didn't end there.

A week later he began experiencing heart problems.

"It was as if someone was playing the drums on the bed — it was just bang, bang, bang, bang, bang."

He was rushed to hospital a second time, this time his heart had gone out of rhythm, what's known as atrial fibrillation.

And in the weeks after the fire, his nasal washes repeatedly came out black with ash.

"For six weeks that [black] soot came out," he said.

|

|

Ash washed on many beaches following last summer's

bushfires. (Supplied: Renee Tonkin) |

"What we also know is that exposure to this sort of particulate matter can have a longer-term impact on things like cardiovascular health," Dr Hunter said.

"So whether you develop a little bit of plaque in your arteries, either in the heart or the brain, or other parts of the body, whether or not there is an association with a slight increase in malignancy and cancers.

"Those are questions we won't know the answer to for another 10 or 20 years."

It is why academics are strongly urging governments to invest in long-term studies.

Climate change a 'big driver'

The royal commission into bushfires made a series of recommendations including aligning air-quality measurements around the country and standardised warnings and health advice.

It also suggested the establishment of "smoke plans" so that communities can evacuate to safe havens such as libraries and shopping centres with air filters.

But many believe dealing with the smoke is just treating the symptom of an underlying condition: climate change.

Concerned emergency services leaders have vowed to make sure the royal commission's recommendations are more than just words.

The group, Emergency Leaders for Climate Action, consisting of retired fire chiefs and health leaders, has launched its own tracker to monitor outcomes.

The tracker is an online list of recommendations of the royal commission with updates about whether they've been implemented and what stage those reforms are at.

"It's very critical that the states don't lose momentum," public health expert David Templeman, who is part of the group, said.

"Climate change is the big driver here; you can't get improvement in air quality unless you address the root cause of it."

Calls for the climate as cause of death

|

|

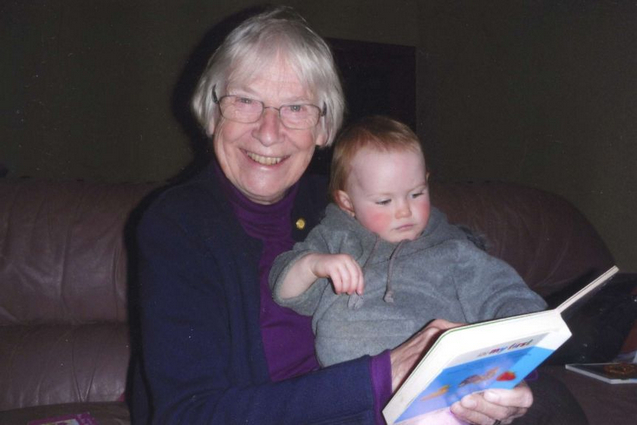

Imogen Jubb said the bushfire smoke caused her mother's health to

decline. (ABC News) |

The retired psychologist had been hospitalised with breathing difficulties in early December and was able to spend Christmas with her family.

"I had no thought that she wouldn't be alive a few weeks later," Ms Jubb said.

Ms Jubb, who works for climate change think tank Beyond Zero Emissions, said as the weeks of smoke dragged into January her mother started to decline.

"She didn't feel comfortable going outside, it was really hot in the house," she said.

|

|

Annemarie Jubb died after last summer's bushfires. (Supplied) |

Medical experts say when patients have several health issues, it's impossible to pinpoint single contributing factor for a health emergency like a heart attack.

Imogen's brother Brendan, a practising paediatrician, believed the air quality was a factor in their mother's death.

"Certainly, she had heart problems to begin with. But the presence of the smoke did make it more difficult for her to breathe," Mr Jubb said.

"She was certainly struggling."

The family wants to see people whose deaths are linked to extreme weather events have climate change listed as an official cause of death on the death certificate, following similar calls from academics at ANU earlier in the year.

"I don't want other communities and other families to have to suffer," Ms Jubb said.

|

|

Brendan Jubb wants climate change listed as an official cause of

death, following similar calls from academics at ANU. (ABC News) |

"Our most recent focus was to ensure that Australia's emissions continued to fall so that we met our 2020 targets," he said.

"And I'm very pleased to say that we managed to do that this year.

"We're now working very hard on meeting Australia's 2030 targets."He said the Federal Government had worked with the states and territories throughout this year to get a consistent approach to air quality readings and warnings as recommended by the commission.

"I can confirm that New South Wales is delivering these improvements to their residents in time for this summer, our hope is that other states and territories are able to do so," Mr Evans said.

He said the Government was giving $2 million to the CSIRO and to the Bureau of Meteorology to work on a smoke forecasting tool and the Government was "open" to the suggestion of smoke plans.

"Those ideas are definitely under consideration by the Government as we speak," he said.

Links

- Climate change is resulting in profound, immediate and worsening health impacts, over 120 researchers say

- Climate Change: 2020 Set To Be One Of The Three Warmest Years On Record

- (AU) Australia Endures Hottest Spring Ever, With Temperatures More Than 2C Above Average

- (AU) Bureau Of Meteorology Says The NT Experienced Its Hottest November In 100 Years

- Sydney Records Hottest November Night As Heatwave Sweeps City

- Born In The Ice Age, Humankind Now Faces The Age Of Fire – And Australia Is On The Frontline

- (AU) The Bushfire Royal Commission Has Made A Clarion Call For Change. Now We Need Politics To Follow

- People who don't have asthma 'using inhalers for the first time', western Sydney GP tells

- Doctors worry 'unprecedented' bushfire smoke creating new health risks