After the turbulent year of 2020, BBC Future takes stock on the state of the climate at the beginning of 2021.

|

|

As the world turns to renewable energy, climate change is already

being felt across the world

(Credit: Getty Images)

|

We have come to a "moment of truth", United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres said in his State of the Planet speech in December. "Covid and climate have brought us to a threshold."

BBC Future brings you our round-up of where we are on climate change at the start of 2021, according to five crucial measures of climate health.

1. CO2 levels

The amount of CO2 in the atmosphere reached record levels in 2020, hitting 417 parts per million in May.

The last time CO2 levels exceeded 400 parts per million was around four million years ago, during the Pliocene era, when global temperatures were 2-4C warmer and sea levels were 10-25 metres (33-82 feet) higher than they are now.

"We are seeing record levels every year," says Ralph Keeling, head of the CO2 programme at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, which has been tracking CO2 concentrations from the Mauna Loa observatory in Hawaii since 1958. "We saw record levels again this year despite Covid."

The effect of lockdowns on concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere was so small that it registers as a "blip", hardly distinguishable from the year-to-year fluctuations of the carbon cycle, according to the World Meteorological Organization, and has had a negligible impact on the overall curve of rising CO2 levels.

"We have put 100ppm of CO2 in the atmosphere in the last 60 years," says Martin Siegert, co-director of the Grantham Institute for climate change and the environment at Imperial College London.

That is 100 times faster than previous natural increases, such as those that occurred towards the end of the last ice age more than 10,000 years ago.

"If we keep tracking the worst-case scenario, by the end of this century levels of CO2 will be 800ppm. We haven't had that for 55 million years. There was no ice on the planet then and it was 12C warmer," says Siegert.

|

|

CO2 emissions have risen rapidly since the 1970s

(Credit: European Commission JRC EDGAR/Crippa et al. 2020/BBC) LARGE IMAGE

|

The past decade was the hottest on record. The year 2020 was more than 1.2C hotter than the average year in the 19th Century. In Europe it was the hottest year ever, while globally 2020 tied with 2016 as the warmest.

Record temperatures, including 2016, usually coincide with an El Niño event (a large band of warm water that forms in the Pacific Ocean every few years), which results in large-scale warming of ocean surface temperatures.

But 2020 was unusual because the world experienced a La Niña event (the reverse of El Niño, with a cooler band of water forming). In other words, without La Niña bringing global temperatures down, 2020 would have been even hotter.

The exceptionally warm temperatures triggered the largest wildfires ever recorded in the US states of California and Colorado, and the "black summer" of fires in eastern Australia.

"The intensity of those fires and number of people being killed is truly significant," says Siegert.

|

|

High temperature anomalies have become greater and more frequent in

recent years on land, air and sea (Credit: NOAA/BBC) LARGE IMAGE

|

Nowhere is that increase in heat more keenly felt than in the Arctic. In June 2020, the temperature reached 38C in eastern Siberia, the hottest ever recorded within the Arctic Circle.

The heatwave accelerated the melting of sea ice in the East Siberian and Laptev seas and delayed the usual Arctic freeze by almost two months.

"You definitely saw the impact of those warm temperatures," says Julienne Stroeve, a polar scientist from University College London.

On the Eurasian side of the Arctic Circle, the ice did not freeze until the end of October, which is unusually late.

The summer of 2020 saw sea ice area at its second lowest on record, and sea ice extent (a larger measure, which includes ocean areas where at least 15% ice appears) also at its second lowest.

As well as being a symptom of climate change, the loss of ice is also a driver of it. Bright white sea ice plays an important role in reflecting heat from the Sun back out into space, a bit like a reflective jacket.

But the Arctic is heating twice as quickly as the rest of the world – and as less ice makes it through the warm summer months, we lose its reflective protection. In its place, large areas of open dark water absorb more heat, fueling global warming further.

Everything is interconnected. If one part of the climate system changes, the rest of the system will respond – Julienne StroeveMulti-year ice is also thicker and more reflective than the thin, dark seasonal ice that is increasingly taking its place. Between 1979-2018, the proportion of Arctic sea ice that is at least five years old declined from 30% to 2%, according to the IPCC.

"White ice reflects a lot of energy from the Sun and helps slow the rate of global warming," says Michael Meredith, a polar researcher at the British Antarctic Survey. "We are accelerating global warming by reducing the amount of Arctic sea ice."

The loss of ice is believed to be disrupting weather patterns around the world already. According to the Grantham Institute, it is possible – though not conclusively shown – that 2018 Arctic conditions provoked the "Beast from the East" winter storm in Europe in 2018 by altering the jet stream, a current of air high in the atmosphere.

"Temperature difference between the equator and poles drives a lot of our large-scale weather systems, including the jet stream," says Stroeve. And because the Arctic is warming faster than lower latitudes, there is a weakening of the jet stream.

"Everything is interconnected. If one part of the climate system changes, the rest of the system will respond," says Stroeve.

|

|

The Arctic sea ice has been diminishing rapidly since detailed

records began in the 1970s, in a feedback cycle of warming and

melting (Credit: NSIDC/BBC) LARGE IMAGE

|

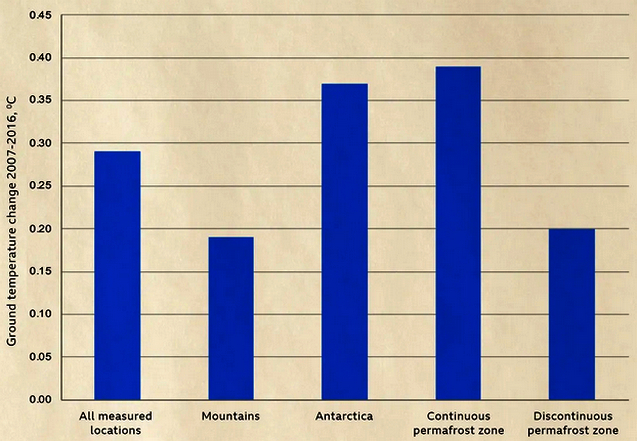

Across the northern hemisphere, permafrost – the ground that remains frozen year-round for two or more years – is warming rapidly.

When air temperatures reached 38C (100F) in Siberia in the summer of 2020, land temperatures in several parts of the Arctic Circle hit a record 45C (113F), accelerating the thawing of permafrost in the region.

Both continuous permafrost (long, uninterrupted stretches of permafrost) and discontinuous (a more fragmented kind) are in decline.

Permafrost contains a huge amount of greenhouse gases, including CO2 and methane, which are released into the atmosphere as it thaws.

Soils in the permafrost region, which spans around 23 million square kilometres (8.9 million square miles) across Siberia, Greenland, Canada and the Arctic, hold twice as much carbon as the atmosphere does – almost 1,600 billion tonnes.

Much of that carbon is stored in the form of methane, a potent greenhouse gas with a global warming impact 84 times higher than CO2.

"Permafrost is doing us a big favour by keeping that carbon locked away from the atmosphere," says Meredith.

Thawing permafrost also damages existing infrastructure and destroys the livelihoods of the indigenous communities who rely on the frozen ground to move around and hunt.

It is thought to have contributed to the collapse of a huge fuel tank in the Russian Arctic in May, which leaked 20,000 tonnes of diesel into a river.

|

|

As ground temperatures rise even fractionally, permafrost around

the world begins to thaw and release greenhouse gases

(Credit: Biskaborn et al. 2019/Nature Communications/BBC) LARGE IMAGE

|

Since 1990 the world has lost 178 million hectares of forest (690,000 square miles) – an area the size of Libya. Over the past three decades, the rate of deforestation has slowed but experts say it isn't fast enough, given the vital role forests play in curbing global warming.

In 2015-20 the annual deforestation rate was 10 million hectares (39,000 square miles, or about the size of Iceland), compared to 12 million hectares (46,000 square miles) in the previous five years.

"Globally forest areas continue to decline," says Bonnie Waring, senior lecturer at the Grantham Institute, noting that there are big regional differences. "We are losing a lot of tropical forests in South America and Africa [and] regaining temperate forests through tree planting or natural regeneration in Europe and Asia."

Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Indonesia are the countries losing forest cover most rapidly. In 2020, deforestation of the Amazon rainforest surged to a 12-year high.

An estimated 45% of all carbon on land is stored in trees and forest soil. "Soils globally contain more carbon than all plants and atmosphere put together," says Waring. When forests are cut down or burned, the soil is disturbed and carbon dioxide is released.

The World Economic Forum launched a campaign this year to plant one trillion trees to absorb carbon. While planting trees might help cancel out the last 10 years of CO2 emissions, it cannot solve the climate crisis on its own, according to Waring.

"Protecting existing forests is even more important than planting new ones. Every time an ecosystem is disturbed, you see carbon lost," she says.

Allowing forests to regrow naturally and rewilding huge areas of land, a process known as natural regeneration, is the most cost-effective and productive way to capture CO2 and boost overall biodiversity, according to Waring.

|

|

World deforestation rates are slowing slowly overall, but in some of

the world's most pristine forests it is still rapid

(Credit: FAO/BBC)

LARGE IMAGE |

As Guterres noted in his December State of the Planet speech, "Let's be clear: Human activities are at the root of our descent towards chaos. But that means human action can help solve it."

Links

- The mystery of Siberia’s exploding craters

- Why the Arctic is smouldering

- The batteries that could make fossil fuels obsolete

- How Iceland is turning CO2 into stone

- How shrubs can fight climate change

- China's massive solar farms transforming world energy

- The rise of zero-carbon shipping

- The people ditching planes for trains

- How to reduce emissions from your fridge

- The revolutionary plan to save the Congo Basin

- The vast rewilding of the Kazakh stepp