Financial Times

- Jamie Smyth

Even as demand falls, federal and state governments are pumping billions

into the polluting fossil fuel industry

|

© Brendon Thorne/Bloomberg

|

Newcastle, Australia

- For more than 200 years, workers at the Port of Newcastle have loaded

ships with coal dug out of nearby mines for transport to Asia and beyond.

But with global action to tackle climate change set to decimate the trade,

the management at the world’s biggest coal port is preparing for a future

without the fossil fuel that generates 60 per cent of its revenues.

“The

future of coal is obviously questionable and we have to prepare for that,”

says Roy Green, chair of the port, which is a gateway to the Hunter Valley,

a coal mining region 280km north of Sydney. “We are likely to see a

continuing flattening of coal volumes through the port and ultimately a

decline, as the world switches away from coal-fired power.”

The

acknowledgment that coal, which is more polluting than any other fuel

source, has a shrinking lifespan is an accepted fact in many boardrooms and

mining communities in Europe, the US and China, where preparations for an

energy transition away from fossil fuels are already under way.

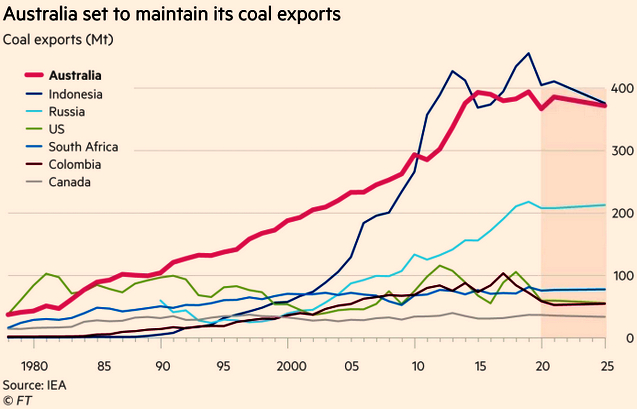

But in Australia, the world’s second-biggest exporter of coal by

volume, discussions around phasing out fossil fuels remain contentious and

risk inflaming the nation’s “climate wars” — a bitter 15-year battle between

conservatives and progressives which has contributed to the ousting of three

prime ministers in recent years.

The government is resisting

international pressure to commit to net zero emissions by 2050 and has ruled

out charging polluters by setting a price on carbon. It opposes the early

closure of ageing coal-powered electricity plants — arguing that relying too

much on renewables could lead to power cuts — and recently funded a

feasibility study on whether to build a new coal plant in Queensland.

“We will not achieve net zero in the cafés, dinner parties

and wine bars of our inner cities . . . [or] by taxing industries, that

provide livelihoods for millions of Australians, off the planet,” Scott

Morrison, Australia’s prime minister, told a business audience on April 20.

Days later Morrison snubbed a request by Joe Biden, the US president, to

join other nations in pledging deeper emissions’ cuts.

Instead

it is the decisions being taken by the world’s biggest coal consumers to

commit to a net zero emissions target by 2050 in the case of Japan and South

Korea, and 2060 for China, that could act as a catalyst for change in

Australia, say critics.

In a growing number of companies and

communities across Australia, the discussion is changing from how to save

coal to the need for a just economic transition to compensate for the loss

of well-paying mining and related jobs. Many fear that if this does not

happen, companies will go bust and people will suffer unnecessarily.

|

Workers at the Port of Newcastle have loaded ships with coal

dug out of nearby mines for transport to Asia and beyond for two

centuries. © Brendon Thorne/Bloomberg

|

Energy Australia, a utility, announced in March that

it would close a coal fired plant in the Latrobe Valley in 2028, four years

earlier than originally planned. AGL, Australia’s largest utility, is also

planning to split off an electricity generating division dominated by

coal-fired power stations, a recognition that fossil fuels have fallen out

of favour with investors.

Some miners, including Rio Tinto and

BHP, have either already exited the market for thermal coal — commonly used

in electricity generation — or signalled their intention to do so. A

collapse in price to $50 per tonne in the second half of 2020 due to weak

demand linked to the coronavirus pandemic and import restrictions slapped on

Australian exports by China have further raised doubts over the future of

the Hunter Valley’s 40 mines, which support about 16,000 jobs.

Critics

warn there is an urgent need for Canberra to show leadership and plan an

orderly transition to guarantee cheap and stable power, help coal mining

regions diversify their economies into areas like agriculture and ensure

Australia does not miss the opportunity to become a leader in green

energies.

Yet Australia’s federal and state governments have in the past year

funnelled A$10.3bn in tax breaks and subsidies to the fossil fuel industry.

Almost three quarters of that came in the form of rebates paid to large

users of fuel, such as miners and farmers, according to a report published

by The Australian Institute, a progressive think-tank. Authorities have also

approved an expansion of a Glencore coal mine just north of the Hunter

Valley and an extra A$264m in funding for carbon capture storage — a

technology that it hopes could extend the life of its coal export industry.

“Australia’s foreign policy for decades has been to undermine

other countries’ ambitions to reduce emissions so that we can continue to

sell enormous amounts of coal and gas,” says Richard Denniss, chief

economist at The Australian Institute. “Australia is not planning a

transition away from fossil fuels.

“What we are actually doing is

trying to maximise profits in the endgame,” he adds. “That’s why there is a

rush to approve new coal mines. We know that in 30 years’ time no one will

be buying coal. But if we flood the market and push the price down, we can

we can still sell some for the next 15 years.”

|

A protester wearing a face mask depicting Scott Morrison, the

prime minister, eats fake coal out of a dog bowl during an

Extinction Rebellion protest in Brisbane in April.

© Darren England/AAP Image/Reuters

|

‘Money to be made in mining’ Any

transition away from fossil fuels will be felt most keenly in places like

Maitland, a blue collar city in the Hunter Valley which owes its rich

architectural heritage to the profits generated in nearby coal fields.

Four coal-fired power plants in the region are scheduled to

close over the next 15 years, as energy companies begin phasing out their

most polluting assets. Local coal miners will experience a modest drop in

demand as a result of the closures, but of greater concern to the industry

are the signs of slowing international demand for Australian thermal coal.

Glencore and BHP, two of the country’s biggest coal producers,

reported combined losses of just over $1bn in their Australian coal

divisions in the six months to the end of December. In March, the Department

of Industry warned that if exporters continued to receive lower prices for

their coal due to Australia’s trade spat with China, production levels at

higher cost mines could be cut.

“There is so much pressure on

coal,” says Gerard Spinks, who has worked in Hunter Valley coal power plants

for more than 40 years, “that I think it’s going to disappear off the face

of the earth in the not too distant future. It’s inevitable.”

He

was one of more than 100 people crammed into a bowling club in a Maitland

suburb in March for the inaugural meeting of the Hunter Jobs Alliance, a

collaboration of trade unions and environmental groups which wants to help

the region prepare for life beyond coal.

|

The then treasurer Scott Morrison, now prime minister,

brandishes a lump of coal during parliamentary questions in

Canberra in 2017.

© AAP Image/Mick Tsikas via Reuters Connect

|

Spinks, a trade union delegate at the Bayswater power station, says three

generations of his family have worked in the coal business but people now

need to be realistic and plan for a future without coal, he says. “We need

to get things in place to ensure there is meaningful work in the valley for

our kids.”

Several speakers focused on the need for policymakers

to grasp opportunities provided by renewable energy, modernise local

infrastructure and invest in education. There was also a plea for an end to

the bitter acrimony which has divided the community into pro- and anti-coal

lobbies over recent years.

“People will still disagree but we

need to create a better quality discussion, to find common ground and not

yell at one another,” says Warrick Jordan, co-ordinator of the Hunter Jobs

Alliance.

Could this year mark a

turning point for climate?

Ideological divisions over the future of coal run deep in Australian

communities, politics and the media. Malcolm Turnbull, who was ousted as

prime minister in 2018 following a failed attempt to reform energy policy,

was sacked in April as chair of the New South Wales government’s Net Zero

Emissions and Clean Economy Board for proposing a moratorium on coal mine

approvals in the Hunter Valley region.

“It’s just thuggery,”

says Turnbull, who blamed rightwing media dominated by Rupert Murdoch’s News

Corp — for waging a vendetta against him and bullying the government to

remove him less than a week after his appointment.

News Corp,

which owns almost 60 per cent of Australia’s national and metropolitan

newspapers, is a staunch supporter of the government and campaigns against

stronger climate action.

“The Murdoch media has spent decades

poisoning both our political and literal atmosphere,” Michael Mann, a US

climate scientist, told an Australian parliamentary committee on media

diversity in April. “The Murdoch press is substantially to blame for serving

as a megaphone of climate disinformation. Disinformation that has provided

fodder for an activist politician, like former US President Donald Trump,

and the current Australian prime minister.”

|

Joel Fitzgibbon, proud owner of gold cufflinks emblazoned with

the letters ‘COAL’, quit Labor’s shadow cabinet in November over

its climate change policy. © Mick Tsikas/Getty

|

News Corp rejects this, with Murdoch telling shareholders in November:

“We do not deny climate change. We’re not deniers.”

Critics

allege the main political parties — Liberal, National and Labor — are

addicted to donations from the fossil fuel industry. In the year up to the

2019 general election, political parties received a record A$85m in

donations from resource companies — 69 per cent of all monies raised — an

analysis of Australian Electoral Commission data by the Grattan Institute

think-tank shows.

Bill Shorten, who resigned as leader following

Labor’s surprise 2019 defeat, blamed “powerful vested interests” including

mining mogul Clive Palmer, who spent more than A$80m on a negative campaign

focused on “Shifty Shorten”. Analysts cite the party’s pledge to cut 2030

emissions by 45 per cent when compared with 2005 levels, as a key factor

that lost Labor coal mining seats in Queensland.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s

coverage here

Labor has since dropped the 2030 target, although

it remains committed to achieving net zero emissions by 2050 — a clear point

of difference from the ruling coalition. But ahead of a general election,

due to be held next year, the party faces internal pressure from MPs in coal

regions not to expand its ambition on climate policies or discuss the

transition from coal.

“There are excessive progressives in my

own party who . . . are trying to change the Labor party, and with some

success, from the party of the workers to the party of climate change,” says

Joel Fitzgibbon, Labor party MP for the Hunter constituency.

Fitzgibbon, the proud owner of gold cufflinks emblazoned with

the letters ‘COAL’, quit Labor’s shadow cabinet in November over its climate

change policy. He is agitating for the party to send a clear signal that it

supports the industry ahead of a state by-election in the area this month,

but critics within Labor say he risks splitting the party.

“Coal

power generation is in transition but coal mining is not . . . There is a

wealth of money to be made in mining,” he says. “And there is no job in the

Hunter that will pay the amount that the miners do . . . semi-skilled miners

earn A$120,000 per year as a base rate.”

|

The Baralaba South coal mine proposal in Queensland has fallen

flat after farmers and traditional owners took their complaints

to the UN. © Paul Stephenson/Reuters

|

The need to diversifyDespite the reticence of

politicians to discuss transition, local businesses are becoming acutely

aware of the need to diversify and are calling for policy changes and

funding to help them do so.

At the Port of Newcastle, where bulk

carriers shipped 158m tonnes of coal last year to China, Japan and a host of

other nations, management is planning a A$2bn investment to build a

deepwater container terminal to boost its non-coal revenues by importing

everything from grain to consumer goods.

Green says the proposal

could transform the port and the state’s economy by reducing costs for

businesses, easing traffic congestion in Sydney and creating new jobs in the

region. He cites a report by Alphabeta, a consultancy, which forecasts the

terminal could provide a A$6bn boost to the local economy and take 750,000

trucks off Sydney roads by 2050. “There are no other deepwater ports on the

east coast that can accommodate the ultra large container vessels, so this

is a very significant opportunity,” he says.

|

A freight train transports coal from the Gunnedah Coal Handling

and Preparation Plant, operated by Whitehaven Coal, in Gunnedah,

New South Wales. © David Gray/Bloomberg

|

But the proposal remains blocked by port commitment deeds agreed by

the New South Wales government when it privatised Botany, Kembla and

Newcastle ports between 2013 and 2014 in transactions that raised A$6.75bn.

Under these 50-year deals, the Port of Newcastle would have to pay

compensation to the state government if it exceeded a cap of handling more

than 30,000 containers a year — rendering its proposed investment uneconomic

and limiting Newcastle’s room to diversify.

Australia’s

competition regulator is challenging the deeds in court but the state

government is refusing to back down, as it could be liable for compensation.

“Now is the time for some innovative thinking from both state and federal

governments to help this region transition and benefit the wider economy,”

says Green.

A ‘technology, not taxes approach’ Under pressure from the EU, which is threatening to impose

carbon tariffs on imports from nations that fail to make ambitious emissions

cuts, the Australian government — which reduced emissions by just 4 per cent

between 2013 and 2021 — has begun to discuss ways to decarbonise the

economy. But it has so far refused to introduce a carbon pricing mechanism,

which is widely considered the most efficient way to reduce emissions.

Instead it wants to rely on new technology to meet its modest target of

26-28 per cent emission cuts by 2030, when compared to 2005 levels.

“We are taking the technology, not taxes approach,” says Keith

Pitt, Australia’s mining minister. “There are more than 200 power stations

either under construction or being designed and planned right now and they

will need to utilise high quality coal and we will look to fulfil that.”

|

Stockpiles of coal at the Newcastle Coal Terminal in March.

© Brendon Thorne/Bloomberg

|

At state government level there are some signs of

progress. New South Wales announced a A$25m fund in April — created from

mining royalties — to help regions develop new industries beyond coal. It

also paid A$100m compensation to Shenhua, the Chinese company, for reversing

planning approval for a mine north of the Hunter Valley following community

opposition, which thwarted the project.

But neither federal nor state governments plan to impose a moratorium on

approving new mines or expansions amid a flurry of proposals by small

miners eager to capitalise on the exits made by Rio and BHP. The

Australian Institute report detailed 23 applications for new developments

with the potential to produce 98m tonnes a year of coal.

“If

approved, these mines risk locking large parts of the Hunter in the past,”

says Denniss, “while failing to plan for the future.”

Links