We are to blame for the biggest extinction event in human history. But there is a solution if we take urgent action now.

|

|

Paradise lost: An estimated 15 to 20 tons of plastic trash wash ashore every single year on a 0.6-mile uninhabited

stretch of Kamilo Beach on the island of Hawaii.

(Photo credit: M. Lamson/Hawaii Wildlife Fund via National Institute of Standards and Technology).

|

|

Author

Reynard Loki

is Editor, Chief Correspondent and Writing Fellow for

Earth | Food | Life. He had previously served as the environment, food and animal rights

editor at AlterNet.

|

We are in the midst of the Sixth Extinction, the biggest loss of species in the history of humankind.

So many species are facing total annihilation. Nearly one-third of freshwater species are facing extinction. So are 40 percent of amphibians. 84 percent of large mammals; a third of reef-building corals; and nearly one-third of oak trees.

Rhinos and elephants are being gunned down at rates so alarming that they could be completely wiped out from the wild by 2034. There may be fewer than 10 vaquita—a kind of porpoise endemic to Mexico’s Gulf of California—due to illegal fishing nets, pesticides and irrigation. There are 130,000 plant species that could become extinct in our lifetimes.

All told, about 28 percent of evaluated plant and animal species across the planet are now at risk of becoming extinct.

The rapid decline in species has occurred in recent years: 60 percent of the planet’s wildlife populations have been lost in just the last 50 years. Scientists warn that in the coming decades, if we don’t take action, more than 1 million species may vanish from the Earth forever.

Our fellow Earthlings are being overhunted, overfished and overharvested for our food, clothing and medicines. And the ones that we don’t kill are losing their homes as we destroy their natural habitats to make space for our farms and cities and to extract fuels, minerals, timber and other resources for human society. And the habitats that we don’t completely eradicate we pollute with a vast array of toxic elements, from pesticides and plastics to carbon dioxide, fracking chemicals and invasive species.

We are even polluting wildlife habitats with our light and noise. And scientists fear that the worst is yet to come. As the International Union for Conservation of Nature warns, the worldwide extinction crisis is “expected to worsen as the human population grows.”

According to the Population Reference Bureau, the world’s human population is expected to reach 9.9 billion by 2050. That’s more than 25 percent more people on the planet than the 7.9 billion people currently living on the Earth. Other species will certainly be squeezed out.

Biodiversity isn’t just nice to have—it’s essential to the health and maintenance of the planet’s ecosystems, which, in turn, are critical to human health. In addition to providing sustenance, medicines and livelihoods to billions of people, biodiversity helps maintain the Earth’s basic life-supporting elements like clean water, clean air and crop pollination, as well as critical ecosystem services like soil fertility, waste decomposition and recovery from natural disasters.

“Whether in a village in the Amazon or a metropolis such as Beijing, humans depend on the services ecosystems provide,” writes Julie Shaw the director of communications of the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, a biodiversity conservation joint initiative of the French Development Agency, Conservation International, the European Union, the Global Environment Facility, the government of Japan and the World Bank.

“Ecosystems weakened by the loss of biodiversity are less likely to deliver those services, especially given the needs of an ever-growing human population.”

|

|

IDL TIFF file

|

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)—a three-decade-old international treaty adopted by 193 countries (not including, most notably, the United States)—points out that “at least 40 percent of the world’s economy and 80 percent of the needs of the poor are derived from biological resources.”

Damian Carrington, the environment editor of the Guardian, writes that ecosystem services are “estimated to be worth trillions of dollars—double the world’s GDP. Biodiversity loss in Europe alone costs the continent about 3 percent of its GDP [$546 million] … a year.”

So what can be done to prevent the rapid extinction of species and protect the world’s biodiversity?

In April 2019, a group of 19 prominent scientists answered that question when they published the “Global Deal for Nature” (GDN), a “time-bound, science-driven plan to save the diversity and abundance of life on Earth,” which, when paired with the Paris Climate Agreement, is meant to “avoid catastrophic climate change, conserve species, and secure essential ecosystem services.”

To achieve its goal of “ensuring a more livable biosphere,” the GDN’s main objective is crystallized in its “30×30” proposal: Conserve 30 percent of the Earth in its natural state by 2030.

The idea has taken off, with 50 nations led by Costa Rica, France and the United Kingdom joining the movement to realize the 30×30 vision of defending big swaths of intact ecosystems from exploitation.

“Protecting 30 percent of the planet will undoubtedly improve the quality of life of our citizens, and help us achieve a fair, decarbonized and resilient society,” said Andrea Meza, Costa Rica’s environmental minister. “Healing and restoring nature is a key step towards human wellbeing, creating millions of quality green and blue jobs and fulfilling the 2030 agenda, particularly as part of our sustainable recovery efforts.”

Nongovernmental organizations have answered the rallying cry as well. The Wyss Foundation, a private charitable foundation based in Washington, D.C., “dedicated to… empower[ing] communities… and strengthen[ing] connections to the land,” has joined forces with National Geographic to launch the Wyss Campaign for Nature—“a $1 billion investment to help [nations], communities, [and] Indigenous peoples” mobilize to achieve the 30×30 goal.

The campaign has launched a public petition urging immediate action to protect those ecosystems that have not yet been completely despoiled by the unrelenting expansion of humanity.

“Protecting 30 percent of our entire planet by 2030 (30×30) is an ambitious but achievable goal,” asserts the campaign. “To achieve it, all countries must embrace the goal and contribute to it; Indigenous rights must be respected; and conservation efforts must be fully funded.”

|

|

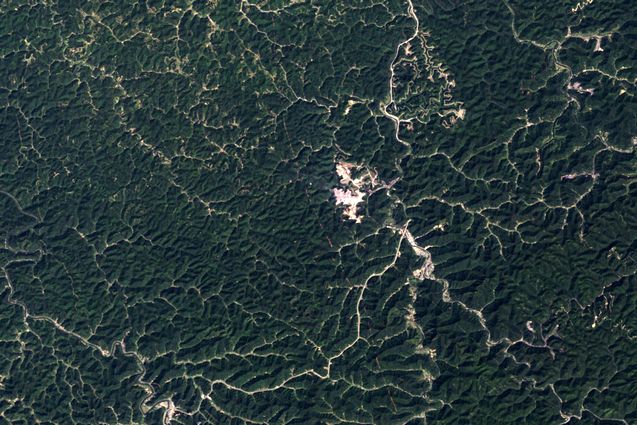

Stripped bare: To access the coal contained in the Appalachian

Mountains in southern West Virginia, extractive companies engage in

a controversial mining method called “mountaintop removal,” which is

as destructive to the ecosystem as it sounds. Scientists have found

that this process negatively impacts groundwater and biodiversity.

(Photo credit: NASA Earth Observatory)

|

“The declaration, under the National Emergencies Act, isn’t just symbolic,” says the Center for Biological Diversity, a conservation nonprofit based in Tucson, Arizona, which has launched a public petition urging the president to take this important and powerful step. “It will unlock key presidential powers to stem the loss of animals and plants in the United States and beyond,” the group says.

Biden’s declaration would marshal the federal resources necessary to start safeguarding the hundreds of species—including the monarch butterfly, eastern gopher tortoise and northern spotted owl—that have been languishing on the waiting list to receive protection under the Endangered Species Act.

Those actions could include directing federal agencies to rein in wildlife exploitation, defend critical wildlife habitat on federal land and use the nation’s economic influence to help protect wildlife habitat around the world from deforestation and environmental damage caused by the private sector.

|

|

Little wise ones: Threatened northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina) fledglings stick close together on a branch. Earlier this year,

the Center for Biological Diversity filed a lawsuit to reinstate federal protections on the species’ essential

habitat covering more than 3.4 million acres of federal old-growth

forests.

(Photo credit: Tom Kogut/USFS/USFWS Endangered Species/Flickr) |

When the 15th Conference of the Parties to the CBD convenes in October in Kunming, China, chances are good that delegates will secure a firm multilateral commitment: The current “zero draft” of the global framework meant to steer conservation efforts through 2030 includes the 30×30 vision as an explicit aim.

“We lose a species to extinction every hour, but extinction is not inevitable,” said Tierra Curry, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity, in December. “We can end extinction with funding and political will. We need to stop making excuses and take the bold policy actions necessary to save life on Earth.”

Cause for concern…

|

|

Killing fields: Oil rigs dot the landscape in Bakersfield,

California, in 2020. In 2019, the state was ranked the seventh-largest producer of crude oil among the 50 states.

(Photo credit: Babette Plana/Flickr)

|

- Renewable energy use is accelerating, but not quickly enough to offset fossil fuel use (The Economist)

- North Carolina pets have high levels of PFAS in blood—has it made them sick? (Greg Barnes, North Carolina Health News)

- Air pollution from farms leads to 17,900 U.S. deaths per year: study (Sarah Kaplan, Washington Post)

Round of applause…

|

|

Pollution pause: In shutting down the Limetree Bay refinery in St.

Croix, President Biden has made a significant step toward fulfilling

his campaign promise to uphold environmental justice.

(Photo credit: vi.gov)

|

Links

- Halting The Extinction Crisis

- Saving Life On Earth A Plan To Halt The Global Extinction Crisis (pdf)

- Global Warming And Life On Earth

- Extinction Countdown

- Smithsonian: Ocean Acidification

- 2020 World Population Data Sheet

- National Park Service: Biodiversity

- Public Health Crisis Looms as California Identifies 600 Communities at Risk of Water-System Failures