This lesser-known greenhouse gas will make or break a “decisive decade” for climate change.

|

| Landfills around the world are one source of rising methane. Others include oil and gas and cows. Omar Havana/Getty Images |

“It’s just like watching a firework show. They’re just popping up all over the place,” said Duren, a University of Arizona scientist who leads the nonprofit Carbon Mapper, which has public and private partners including NASA, the state of California, and the company Planet.

In the public conversation about climate change, methane has gotten too little attention for too long. Many people may be unaware that humans have been spewing a greenhouse gas that’s even more potent than carbon dioxide into the atmosphere at a rate not seen in at least 800,000 years. It harms air quality and comes from sources as varied as oil and gas pipelines to landfills and cows. But methane and other greenhouse gases, including hydroflurocarbons, ozone, nitrogen dioxides, and sulfur oxides, are finally getting the attention they deserve — thanks largely to advances in the science.

Until the past few years, methane’s relative obscurity made sense. Carbon dioxide (CO2) is by far the largest contributor to climate change, and it comes from recognizable fossil fuel sources such as car tailpipes, coal smokestacks, and burning gas and oil. The most troubling part is that it sticks around in the atmosphere for hundreds of years, making climate change not just a problem for us now, but generations well into the future. Carbon is now embedded in our language, from “carbon footprint” to “zero-carbon lifestyle.”

A landmark new report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a UN panel of top climate scientists, marks the first time the global body devotes substantial attention to the major role of gases other than CO2. Its sixth assessment of the science of climate change, which finds that the evidence of man-made warming is “unequivocal” and many climate impacts will be irreversible, dedicates a full chapter of the report to “short-lived pollutants” such as methane. One of their most common sources is fossil fuels.

Global Methane Assessment released this year. It’s fallen “between the cracks” in global research thus far, Shindell says.

Methane has literally fallen between the cracks: Some of it leaks out of the ground in places like oil fields and permafrost, and scientists are still trying to understand where it all comes from. The IPCC report reflects these uncertainties. The chapter authors, for example, do not name the dominant source of human-caused methane emissions, whether fossil fuels or agriculture. But what we now know represents one of the greatest evolutions in climate research since the last IPCC assessment came out in 2013. The work of scientists like Duren helps the world understand the biggest culprits of the methane crisis, in hopes that governments and corporations take urgent action.

Even though methane is not nearly as well understood as carbon, it’s playing an enormous role in the climate crisis. It’s at least 80 times as effective at trapping heat than carbon in a 20-year period, but starts to dissipate in the atmosphere in a matter of years. If this is the “decisive decade” to take action, as the Biden administration has said, then a methane strategy has to be at the center of any policy for tackling global warming.

Methane could mean the difference between a rapidly warming planet changing too quickly and drastically for humanity to handle, and buying the planet some much-needed time to get a handle on the longer-term problem of fossil fuels and carbon pollution.

Methane pollution erases gains from switching off of coal

Shindell, one of the scientists who raised an early alarm about methane, was studying air pollution in the late 2000s when he found a strange trend. Ground-level ozone, the pollutant that forms hazy smog, was rising in the US — which surprised him after decades of progress under the Clean Air Act. He realized the “relentless growth in methane,” which accelerates the formation of ozone near the ground, was to blame. Ever since, he’s been trying to warn the world not to overlook this dangerous pollutant and its costs to both the climate and human health.

Identifying the millions of sources of methane around the globe isn’t so simple. Cattle release methane, and so does decomposing organic material. All the food waste that goes into landfills release methane. And natural gas is almost entirely methane.

If you’ve heard politicians call natural gas a “bridge fuel,” what they mean is that natural gas emits less carbon dioxide than coal. It’s wrong to call it clean, because burning methane still releases carbon — and methane that escapes without burning is a powerful warmer.

60 percent more methane than the Environmental Protection Agency estimates. University of Michigan scientist Eric Kort found methane spewing from offshore wells at far higher rates than previously understood. The environmental group Earthworks, using expensive, on-the-ground camera equipment, helped track down some sites that were repeat offenders of venting methane into the atmosphere.

The scientific papers have mounted: Since 2013, at least 45 scientific papers have highlighted the disproportionate role of oil and gas operations, according to a review by the advocacy group Climate Nexus. Scientists like Duren have also produced vivid images of methane that a layperson can understand, just like the imagery below from April this year.

This false color scene shows a series of methane plumes detected by the Global Airborne Observatory (over laid on Google Earth imagery) from an altitude of 17,500 ft (~5.3 km). The red plumes indicate methane emissions from oil & gas infrastructure.

According to Duren, Carbon Mapper has detected over 3,000 methane plumes in the Permian Basin with its airborne surveys, all coming from a range of oil and gas infrastructure, including wells, tank batteries, compressor stations, pipelines, and more.

Together, these findings suggest a grim outlook for the minimal progress made so far in tackling carbon pollution: Rising methane pollution effectively erases some of the progress the US has made by cleaning up the coal-fired power sector.

The IPCC report noted that methane has been rapidly climbing since 2007, driven by a mix of agriculture (from East and West Asia, Brazil, and northern Africa) and fossil fuels, specifically from North America. In other words, scientists are confident that humans are the main cause of increasing methane pollution.

Still, the data needs to get better. The Trump administration scrapped early rules that would’ve required oil companies to monitor and fix their own leaks. Few major economies even measure methane. China has launched a carbon-trading market to tackle carbon emissions, but has done less to control methane, which comes not just from gas but coal as well.

Scientists know a lot about CO2 — and much less about other gases

There are other greenhouse gases out there besides CO2 and methane. Nitrogen dioxides, black carbon, and halogenated gases (a category that includes chemicals used for refrigerants, hydrofluorocarbons) are other contributors to climate change.

A graphic from the IPCC’s summary for policymakers makes sense of how all these gases interact to add up to at least 1.1 degrees Celsius of average global warming since the 1850s. As the below graphic shows, CO2 and methane make up most of the warming, but other pollutants leave their mark too. Some aerosols from fossil fuels, like sulfur dioxide, actually have a cooling effect (but are dangerous to our lungs).

|

| Other pollutants besides carbon have a heating effect on the atmosphere. IPCC AR6 Summary for Policymakers |

First the bad: Methane is rising, and there’s plenty we don’t know about it. Even if we pinpointed the worst offenders in oil and gas, its other sources would still require sweeping societal change, like a reduction in the number of cows raised for food. (There’s been some experimentation with feed for cattle to reduce methane, or more wackily, fart-collecting backpacks for cows).

Food waste, which releases methane as it decomposes, is a problem too. Across the world, the richest economies are throwing out half their food. Landfills may be able to capture some of the methane, but that too is an energy-intensive process.

|

| Even though methane is not nearly as well-understood as carbon, it’s playing an enormous role in the climate crisis. Patricia Monteiro/Bloomberg via Getty Images |

The whole system is extremely leaky, but the leakiest parts are not totally clear. “It’s just been really hard to put our finger on exactly the source, and be able to attribute it to the granularity that would enable us to solve it,” said Fran Reuland, a researcher on methane in the oil and gas industry at the think tank RMI. “Because it’s happening over such a large area, wrapping your mind around just how much is coming out is one of the main problems.”

Another frustrating challenge is that methane emissions fluctuate. Carbon Mapper pieced together a time series of a section of the Permian Basin in the southwestern US, in which the dots corresponding with methane emissions. About half the time, Duren estimates, some of the worst offenders may be venting methane directly into the atmosphere to relieve pressure, while the other half probably represent persistent leaks and malfunctions.

This time series illustrates the importance of frequent monitoring of highly intermittent (but high magnitude) methane point source emissions. This represents several weeks of daily surveys of a ~ 6000 km2 area in the Permian basin.

Environmentalists argue we must transition off coal, gas, and oil as quickly as possible — but stopping the pollution can’t wait for the transition to play out. A coalition of 134 environmental and health groups have rallied around a certain target — cutting 65 percent of the oil and gas industry’s methane pollution by 2025 — and have pressured the Biden administration to adopt the same goal by using existing technology.

The gains from containing methane will be critical as the world continues to gamble with its climate. A study from EDF scientists published in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Research Letters found that tackling methane emissions across multiple sectors, including oil and gas, agriculture, and landfills, can slow the current rate of runaway warming by a staggering 30 percent. One-quarter of one degree Celsius by 2050 might not sound like a lot, but small changes to global averages contain a range of extreme impacts that will worsen across the globe.

There’s the good news: The world doesn’t need to wait around for better science. Action is feasible now.

|

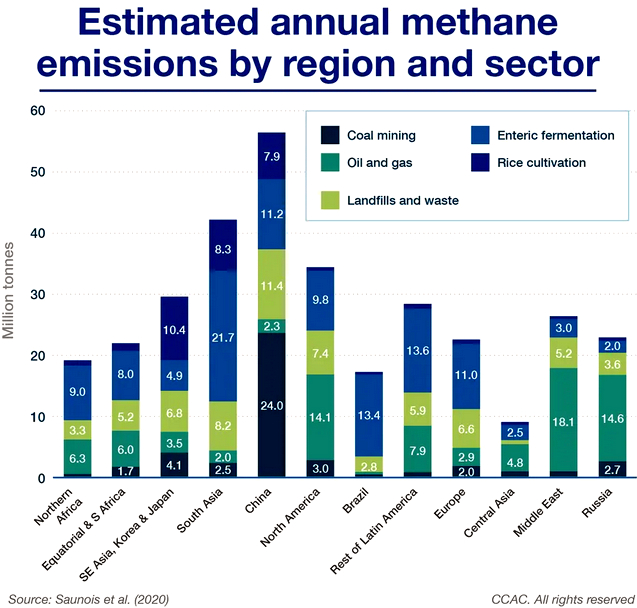

| Estimates of methane’s biggest sources from human activity around the world. In North America, the biggest source is fossil fuels. UN Global Methane Assessment, 2021 |

When the IPCC report came out on August 9, Lisa DeVille, a member of the Dakota Resource Council who lives on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, was encouraged to hear scientists “echoing what most of us can see with our own eyes,” based on what she sees on the front lines of oil production in North Dakota.

“The land near my home is crisscrossed with oil and gas pipelines, literally littered with drilling rigs,” DeVille said in a call with reporters. She said her home has been ravaged by unusually high rainfall and flooding, and she and her husband have had to breathe in smoke from wildfires. “I live less than a mile away from well pads that vent and flare methane and choke our atmosphere, making local people like my husband and I sick. This means the land that is part of my identity as an Indigenous women has been turned into a pollution-filled industrial zone.”

Under pressure from climate advocates, the Environmental Protection Agency is expected to pass a new set of rules in September. Environmentalists have pushed for high targets, and hope these rules will require oil and gas companies to both monitor and address methane leaks from existing and future wells, using sensors and regular equipment checks. The Biden administration has suggested that methane regulation offers “near-term solutions” to climate change.

There’s widespread agreement, even from some in the fossil fuel industry, that the place to start is tackling leaks. This will get easier as scientists gather better data about where methane is leaking. From the industry’s perspective, companies are losing product and dollars. For activists, plugging leaks is one step on the road to permanently phasing out gas.

The problem that underlies all of climate action is that humanity has to trade short-term profit for the long-term costs. Carbon pollution affects the world for the long haul, and methane is making the crisis significantly worse in the near term.

On the plus side, tackling methane and other dangerous pollutants would have an “immediate payoff,” said Global Methane Assessment’s Shindell. It could change our dangerous climate trajectory over the next 30 years.

“Every action counts,” said Jane Lubchenco, a senior science adviser to the Biden administration, in an interview with Vox. “Every avoided tenth of a degree matters.”

Fractions of degrees could translate into wild swings in extreme weather, or tipping points we don’t even fully understand. In the effort to prevent climate catastrophe, methane will count tremendously.

Links

- (EDF) New IPCC Report Zeroes In On Urgency Of Reducing Methane

- (Big Think) Hey, Methane Leakers: Now We Know Where You Live

- (USA New Yorker) It’s Time To Kick Gas

- (NY Times) Halting The Vast Release Of Methane Is Critical For Climate, U.N. Says

- Carbon Dioxide Levels Are At A 3.6 Million Year High

- NASA Just Released The First Direct Evidence That Humans Are Causing Climate Change

- Land In Russia’s Arctic Blows ‘Like a Bottle Of Champagne’

- There’s a ticking climate time bomb in West Texas

- Where extreme weather is getting even worse, in one map