Droughts and floods forcing workers from rural areas, leading to their exploitation in cities, report warns

|

|

Flooding in Lalmonirhat, Bangladesh. Desperate to cross to India

for jobs, many victims of traffickers are forced into sweatshops or

prostitution. Photograph: Barcroft Media/Getty |

The climate crisis and the increasing frequency of extreme weather disasters including floods, droughts and megafires are having a devastating effect on the livelihoods of people already living in poverty and making them more vulnerable to slavery, according to the report, published today.

Researchers from the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) and Anti-Slavery International found that drought in northern Ghana had led young men and women to migrate to major cities.

Many women begin working as porters and are at risk of trafficking, sexual exploitation and debt bondage – a form of modern slavery in which workers are trapped in work and exploited to pay off a huge debt.

|

|

Children working in an aluminium pot factory in Dhaka,

Bangladesh. Up to 85 million children work in hazardous jobs

around the world. Photograph: NurPhoto/Getty |

She said: “Working as a kayayie has not been easy for me. When I came here, I did not know anything about the work. I was told that the woman providing our pans will also feed us and give us accommodation. However, all my earnings go to her and only sometimes will she give me a small part of the money I’ve earned.”

She dropped a customer’s items once and had to pay for the damage, which she could not afford. The woman in charge paid up on condition that she repay her. She added: “I have been working endlessly and have not been able to repay.”

A woman from the Sundarbans in Bangladesh, who moved to Kolkata after a cyclone to support her family. Now she cannot return to home without her employer’s permission. Photograph: Somnath Hazra A woman from the Sundarbans in Bangladesh, who moved to Kolkata after a cyclone to support her family. Now she cannot return to home without her employer’s permission. Photograph: Somnath Hazra

|

With countries in the region tightening immigration restrictions, researchers found that smugglers and traffickers operating in the disaster-prone region were targeting widows and men desperate to cross the border to India to find employment and income.

Trafficking victims were often forced into hard labour and prostitution, with some working in sweatshops along the border.

Fran Witt, a climate change and modern slavery adviser at Anti-Slavery International, said: “Our research shows the domino effect of climate change on millions of people’s lives.

Extreme weather events contribute to environmental destruction, forcing people to leave their homes and leaving them vulnerable to trafficking, exploitation and slavery.”

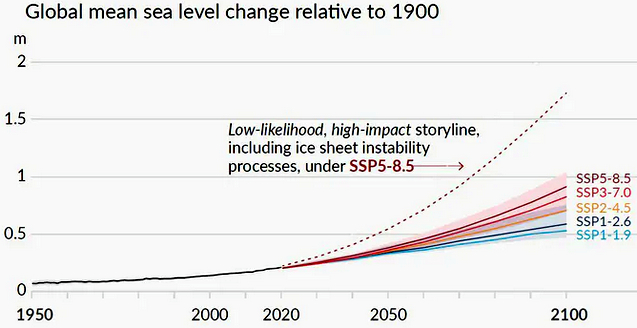

The World Bank estimates that, by 2050, the impact of the climate crisis, such as poor crop yields, a lack of water and rising sea levels, will force more than 216 million people across six regions, including sub-Saharan Africa, south Asia and Latin America, from their homes.

|

The report says labour and migrant rights abuses are disregardedin the interests of rapid economic growth and development.

Ritu Bharadwaj, a researcher for the IIED, said: “The world cannot continue to turn a blind eye to the forced labour, modern slavery and human trafficking that’s being fuelled by climate change. Addressing these issues needs to be part and parcel of global plans to tackle climate change.”

Links

- Climate Change Could Force 216 Million People to Migrate Within Their Own Countries by 2050

- International Institute for Environment and Development

- Climate-induced migration and vulnerability to modern slavery

- Anti-Slavery International

- Slavery & Human Trafficking Booming Thanks To Climate Change Induced Migrations