Indian Express

-

Mira Patel

2021 was supposed to be a year of hope for climate activists but instead,

it turned out being a wasted opportunity for governments.

The year was

marked with climate disasters ranging from extreme wildfires in the American

Southwest to record levels of flooding in Europe.

Coal production increased

sharply and carbon emissions bounced back from 2020 lows as economies slowly

recovered from the pandemic.

In India, the situation is particularly

concerning with nine out of ten most polluted cities in the world located

within the country.

|

This year was marked by a series of climate disasters.

(AP Photos/edited by Abhishek Mitra)

|

This year was a mixed bag for climate activists. There were devastating weather

events that highlighted the dangers of a rapidly warming planet.

Lockdown-induced blue skies and clear air that showed the potential for a

cleaner future. Ambitious plans bookending failed promises. And, in-keeping with

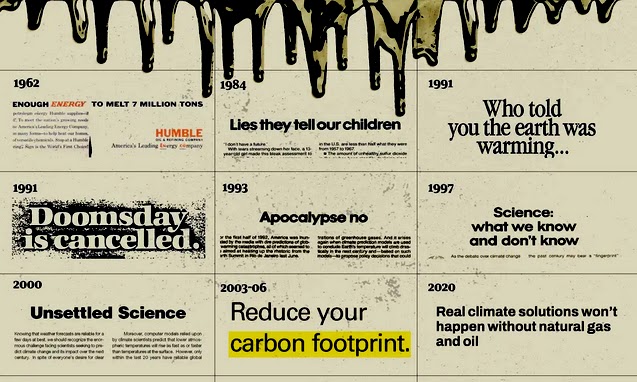

the zeitgeist of our times, some of us continue believing with fear that humans

are destroying the earth, while others dismiss those beliefs as conspiratorial

rhetoric.

From the vantage point of a country where emissions are projected to double or

even triple in the next three decades, Indians have reason for both hope and

fear. Our rapid urbanisation could be an opportunity for us to experiment with

green, technologically advanced cities whereas our rapid population growth could

facilitate an economic model of development at any cost.

India has rightly

argued that as a maturing economy, responsible for far fewer emissions per

capita than our friends in the West, we should be given some if not the same

leeway that industrialised countries have enjoyed in the past.

That argument, while compelling, comes at a steep price. This year, the UN’s

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published a report stating that

humans have “unequivocally” caused the climate crisis and that “widespread and

rapid changes” have already occurred, some irreversibly. UN Secretary General,

António Guterres described the report as “a code red for humanity”. Looking back

at the events of the past year, his sentiments seem far from hyperbole

Fire and floods

According to Anjali Jaiswal, a Senior Director at the Natural

Resources Defense Council (NRDC), who spoke with

indianexpress.com, “the climate crisis is hitting us in the face” and the vulnerable continue to

suffer the most. Sanjay Vashist, Director of the Climate Action Network for

South Asia, added that earlier there were only natural disasters and now there

are mostly man-made disasters.

|

Bare trees stand in a destroyed forest near the Kemerkoy Power

Plant, a coal-fueled power plant, in Milas, Mugla in southwest

Turkey (AP)

|

In 2021, Greece and the Western United States faced crippling forest fires which

burned almost three million acres of land and displaced thousands of people from

their homes. In California, which is particularly vulnerable to climate shocks,

the drought levels were more extreme than at any point in the state’s 126-year

record.

In opposite circumstances, in Tennessee, staggering amounts of rainfall

led to flash flooding that killed more than two dozen people. According to one

Buzzfeed

investigation, between 500 and 1,000 people died during a historic deep freeze in Texas in

February. Scientists say that those events would be “virtually impossible”

without human caused climate change.

There was also a drought in Kenya, a deficiency of rainfall in Turkey, massive

rains in Serbia, catastrophic flooding in China and deadly storms in Germany and

Belgium. In Canada, an entire town was erased by a wildfire fuelled by extreme

heat. In India, rainfall wreaked havoc in Mumbai, while the polluted Yamuna

River in Delhi became covered in foam due to people dumping heavy sewage and

industrial waste into the river.

According to the IPCC report, events like these

which previously occurred around once a decade, are now happening 70 per cent

more frequently.

To put it simply, there is no margin for error. Experts warn that we are

currently on track to raise the earth’s temperature by 2.4C on average since the

pre-industrial era. The last time hotter than now was at least 125,000 years

ago. The world has already heated by 1.2C on average and at 1.5C, countries like

the Maldives will cease to exist. Beyond 1.5C the Middle East could become

uninhabitable, along with large parts of India and China.

At 2C, heatwaves will

become commonplace and virtually all of Europe and North America will have to

contend with frequent wildfires. According to the World Bank, if we continue

along our current trajectory, by 2050, 216 million people will be displaced, a

third of the world’s food production will be at risk and $23 trillion will be

wiped from the global economy.

2021 Recapped

Before looking at the positives, let’s examine the negatives from the past

year.

The first is the increase in fossil fuel production and consumption in 2021.

According to Vashist, governments were preoccupied with the responsibility of

stimulating economic recovery from the pandemic and chose to do so by mining

fossil fuels at a greater rate.

In addition to its general environmental

implications, this can be problematic as according to Vashist because “private

companies don’t mine as per the law but instead, as per their convenience”.

Fossil fuels are on the rise with the amount of energy generated from coal power

plants alone per annum soaring from four per cent in 2020 to nine per cent in

2021. By 2022, worldwide coal demand could reach an all-time high according to

the International Energy Agency.

In the past year, European gas prices increased by 611 per cent in light of a

global energy crunch.

Reports

published by the Economist suggest that this increase reveals that the world

remains poorly prepared to transition into a purely renewable based economy. The

argument is that countries have already accumulated noteworthy renewable

projects but when the oil or natural gas dries up, renewables are helpless to

prevent economies from falling to their knees.

Without rapid reforms, the report

warns that there will be more energy crises which would potentially mobilise a

popular revolt against climate policies and undo much of the progress that has

been made.

Putin has also had an eventful year when it comes to climate change. Already one

of the biggest natural gas exporters in the world, Russia, against liberal

opposition, managed to continue with its Nord stream 2 pipeline, which would

bring Russian natural gas to German households. Right now, Russia is the source

of 41 per cent of Europe’s gas exports.

Additionally, a report from research

firm Bernstien, the global shortage in LNG capacity could rise from 2 per cent

of demand now to 14 per cent by 2030. Unless other nations start aggressively

exporting their own LNG, Russia will continue to dominate the market, rendering

large economies susceptible to the whims and fancies of the Kremlin.

Russia is

just one example of an authoritarian government threatening the safety of global

energy chains, the same can be said of Iran, Egypt and Saudi Arabia. As

democracy backslides, autocracies rise. And when autocratic leaders monopolise

valuable commodities, it is always a cause for concern.

Biodiversity loss is also a significant problem. Trees absorb 11 billion tonnes

of carbon dioxide or 27 per cent of what human industry and agriculture emits.

In a close second, oceans absorb another 10 billion. Destruction of natural

habitats through human activity and overfishing reduces the number of natural

climate sinks and puts us at greater risk for climate disasters

In Brazil, home to the Amazon rainforest (one such climate sink), over 13,00

square kilometres of forest were lost between August 2020 and July 2021. That

marks an increase of 22 per cent from the previous year.

According to a

report

in Foreign Affairs Magazine, under President Jair Bolsenaro, Brazil is

implementing policies that “risk tipping the region into an ecological death

spiral that could cause the release of hundreds of billions of tons of carbon

dioxide into the atmosphere, wipe out ten percent of global biodiversity, and

destroy a forest system that is essential to regulating the entire region’s

rainfall.”

Similar destructive policies threaten the climate and it is worth

noting that while Brazil signed a pledge to end deforestation by 2030, India

refused to do so.

Lastly, 2021 was arguably the year of cryptocurrency. A Cambridge University

study

published in February claimed that bitcoin mining alone, at the time, possessed

a carbon footprint equivalent to Argentina’s. As more countries and institutions

adopt crypto friendly policies, the strain on the environment from mining could

increase tenfold.

This may not sound as ominous as some of the examples

described above, but it is a serious problem, and one that is only going to get

worse.

On to the positives. According to Vashist, one of the biggest developments of

the year was Biden agreeing to re-join the Paris Climate Agreement. That, along

with statements from other top policymakers, indicate that “they have recognised

the importance of attaching a climate lens to the development agenda.”

India has

also made considerable strides in 2021 with PM

Narendra Modi

recently announcing that we would achieve 500GW of non-fossil fuel generated

energy, a feat that would severely reduce our dependence on coal.

In September, Iceland opened the world’s largest carbon sucking machine, Orca,

which is designed to remove 4000 tons of CO2 from the atmosphere each year. In a

landmark ruling in the Netherlands, oil company Shell was ordered to reduce its

emissions by 45 per cent by 2030, relative to 2019 levels.

In March, the world’s

first floating wind farm was opened off the coast of Scotland and in April, JP

Morgan set a goal to finance $2.5 trillion in the next decade to combat climate

change. Bank of America and Citigroup later made similar pledges.

In September,

China announced that it would start enforcing the 2016 Kigali Agreement, vowing

to immediately stop emitting HFC-23, a greenhouse gas 14,600 times more powerful

than CO2. It also announced that it would stop funding oversea coal projects,

with the cancellation estimated to avert three months’ worth of global

greenhouse gas emissions.

With the negatives and positives covered, we can move on to the biggest mixed

bag of the year – the COP26 Summit, an annual meeting of world leaders to

discuss issues pertaining to our climate.

COP26

The COP26 summit was held in Scotland this November to great

expectation from climate activists. The resulting Glasgow Climate Pact was

significant in its recognition that fossil fuels need to be phased out, but

ultimately not enough to halt the rapid warming of the earth to unsustainable

levels.

The pact called for a faster phasing down of the use of coal and the scrapping

of subsidies for fossil fuels. States such as Brazil and Indonesia have signed

on to an agreement to end deforestation by 2030, and have recognised that

indigenous people are best positioned to care for the forests they live in.

The

governments also agreed to beef up their respective national plans for reducing

emissions over the coming decade, before meeting for the COP27 summit in 2022.

|

Indian minister for Environment and Climate Change Bhupender Yadav

attends a stocktaking plenary session at the COP26 U.N. Climate

Summit in Glasgow, Scotland (AP)

|

India has also been praised for its climate leadership at the summit. Jaiswal

states that “India stepped up with bold pledges to cut climate pollution by a

billion tons, in large part by meeting 50 percent of its energy requirements

with renewable energy by 2030, signaling a strong commitment to a healthier and

cleaner future, for the people of India and the world.”

Vashist agrees, noting

that India has been much closer to meeting it’s “fair share” of obligations,

committing, in relative terms, far more than countries like the US and UK. The

NRDC further argues that India is very close to meeting its Paris Agreement

targets and by doing so, is sending a strong message to the world that it is

committed to decarbonisation.

However, for many, the promises derived from the COP26 were not enough. For one,

they are non-binding, and in the past, commitments made during similar summits

have infrequently been upheld.

Secondly, the gap in tons of CO2 between the

emission reductions built into the agreement, and those required to avoid more

than 1.5C of global warming, is roughly 17-20 billion tons of CO2e per year.

Developing nations were also left disappointed with the lack of climate

financing.

Although the Glasgow Agreement promises $356 million in climate

financing, according to one Council on Foreign Relations (CFR)

report, “funding levels remain woefully inadequate.”

Challenges and recommendations

As highlighted above, climate financing is urgently needed in order

for developing countries to transition into renewable energy sources. The UN

Environment Program estimates that developing nations would require $300 billion

per year by 2030 to cope with climate change, far less than what they are

projected to receive.

Equally concerning is where the funds are deployed.

According to the CFR report, the vast majority of funding goes towards

mitigation efforts while adaptation measures are left behind. The difference is

important. Adaptation allows countries to prepare and work towards eliminating

climate disasters, whereas mitigation aims to lessen their impact.

Take for

example, you worry about a car crash occurring due to a pothole on the road.

Adaptation would be getting that pothole fixed while mitigation would be like

keeping a medical kit handy, in case the situation arises.

Vashist amongst

others argue that it is a huge mistake to prioritise mitigation over adaptation.

Adaptation must be a priority, he warns, or poorer nations and vulnerable

populations will be most at risk of climate disasters.

In countries like India, Vashist also asserts that the needs of communities

dependent on fossil fuels should be balanced against the needs of the

environment. This goes back to the fair share argument, which stipulates that

the needs of people in the global south should not be compromised unjustly

relative to those of the West.

While the situation is certainly bleak, there are solutions that can mitigate

the climate crisis. Climate financing needs to become a priority, and more money

needs to be diverted to adaptation. One Foreign Affairs

article

notes that adaptation methods can be hyper localised and low-cost. It states

that “individual communities and cities can take the lead on their own” by

implementing small and simple innovations like painting rooftops white to reduce

the heat that they absorb.

Additionally, it states that adaptation can consist

of “maintaining the natural environment – the forests, coral reefs and coastal

wetlands that provide just as much protection against disaster as manmade

measures do.”

However, man made innovations towards decarbonisation also need to

be promoted which, according to another Foreign Affairs article, will include

investments in electric power, transportation, heating, and agriculture.

Governments also need to redesign energy markets to absorb shortages and to

transition from coal to oil to natural gas to renewables. This would include

long term subsidies for renewables, investment in battery storage, and a

diversification supply.

According to Vashist, the key to this is not blaming fossil fuel suppliers, but

instead, convincing them to transition into green energy. He also notes that

so-called green energy solutions need to be carefully evaluated, with nuclear

energy in particular coming with a host of its own problems.

In terms of

renewables, he states that “solar and wind are the most promising” with the

former especially important.

Jaiswal argues that as we look ahead, “we need more action and less talk, to

implement far reaching climate solutions from India as well as the U.S., China,

and all major economies.” She goes on to stress that we need “government,

business, and civil society to move into action with the urgency of now,

otherwise, the climate crisis will snowball into catastrophic and irreparable

devastation for the whole planet”.

Links