The Conversation

- Bruce Glavovic | Iain White | Tim Smith

|

Mario Tama/Getty Images

|

|

Authors

-

Bruce Glavovic

Professor, Massey University

-

Iain White

Professor of Environmental Planning, University of

Waikato

-

Tim Smith

Professor and ARC Future Fellow, University of the

Sunshine Coast

|

Decades of scientific evidence demonstrate unequivocally that human activities

jeopardise life on Earth. Dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate

system compounds many other drivers of global change.

Governments concur: the science is settled. But governments have failed to act

at the scale and pace required. What should climate change scientists do?

There is an unwritten social contract between science and society. Public

investment in science is intended to improve understanding about our world and

support beneficial societal outcomes. However, for climate change, the

science-society contract is now broken.

The failure to act decisively is an indictment on governments and political

leaders across the board, but climate change scientists cannot be absolved of

responsibility.

As we write in an

article about this conundrum, the tragedy is the compulsion to provide ever more evidence when the

phenomena are well understood and the science widely accepted. The tragedy is

being gaslighted into thinking the impasse is somehow our fault, and we need to

do science differently: crafting new scientific institutions, strategies,

collaborations and methodologies.

Yet, global carbon dioxide emissions are

60% higher today

than they were in 1990, when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (

IPCC) published its first assessment. At some point we need to recognise the

problem is political and that further climate change science may even divert

attention away from where the problem truly lies.

|

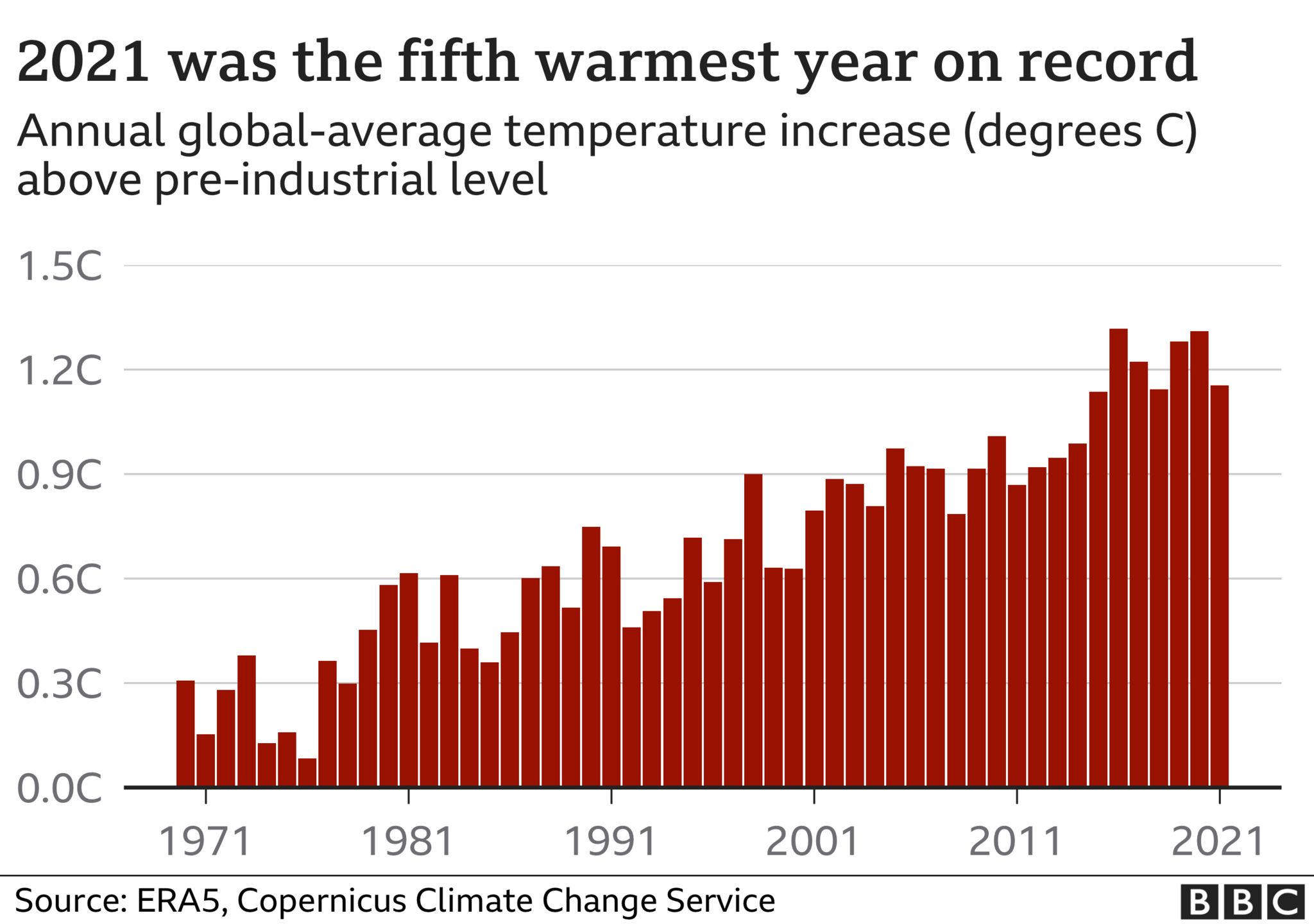

Governments agree that the science is settled but scientists are

compelled to do more research despite inadequate government action

and worsening climate change. Author provided, CC BY-ND

|

Was COP26 too little, too late?

The outcome of COP26, summarised in the draft

Glasgow Climate Pact, includes some progress, including an agreement to begin reducing coal-fired

power, removing subsidies on other fossil fuels, and a commitment to double

adaptation finance to improve climate resilience for countries with the lowest

incomes.

But many of the world’s leading scientists argue that this is

too little, too late. They note the failure of COP26 to translate the 2015

Paris Agreement

into practical reality to keep global warming below 1.5℃ above pre-industrial

levels.

Even if COP26 commitments are fulfilled, there is a strong likelihood that

humanity and life on Earth face a precarious future.

What are climate change scientists to do in the face of this evidence? We see

three possible options — two that are untenable, one that is unpalatable.

Where to from here for climate change scientists?

The first option is to collect more evidence and hope for action. Continue the

IPCC process that stays politically neutral and abstains from policy

prescriptions. A recent

editorial in Nature

called on scientists to do just that: stay engaged to support future climate

COPs.

However, this choice not only ignores the complex relationship between science

and policy, it runs counter to the logic of our scientific training to reflect

and act on the evidence. We know why global warming is happening and what to do.

We have known for a long time.

Governments just haven’t taken the necessary action. In a recent Nature

survey, six in

ten of the IPCC scientists who responded expect 3℃ warming above pre-industrial

levels by 2100. Persisting with this first option is therefore untenable.

The second option is more intensive social science research and climate change

advocacy. As Harvard historian Naomi Oreskes recently

observed, the work of the IPCC’s Working Group I (

WGI, on the physical science basis of climate change) is complete and should be

closed down. Attention needs to focus on translating this understanding into

action, which is the realm of WGII (on impacts, adaptation and vulnerability)

and WGIII (on mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions).

In parallel, growing numbers of scientists are getting involved in diverse forms

of advocacy, including

non-violent civil disobedience.

However, albeit more promising than option one, there is little evidence of

impact thus far and it is doubtful this pathway will lead to the urgent

transformative actions required. This option is also not tenable.

Halt on IPCC work until governments do their part

The third option is much more radical, but unpalatable. We call for a moratorium

on climate change research that does little more than document global warming

and maladaptation.

Attention needs to focus on exposing and re-negotiating the broken

science-society contract. Given the rupture to the contract outlined here, we

call for a halt on all further IPCC assessments until governments are willing to

fulfil their responsibilities in good faith and mobilise action to secure a safe

level of global warming. This option is the only way to overcome the tragedy of

climate change science.

Readers might agree with our framing of this tragedy but disagree with our

assessment of options. Some may want greater detail on what a moratorium could

encompass or worry it may damage the credibility and objectivity of the

scientific community.

However, we question whether it is our “duty” to use public funds to continue to

refine the state of climate change knowledge (which is unlikely to lead to the

actions required), or whether a more radical approach will serve society better.

We have reached a critical juncture for humanity and the planet. Given the

unfolding tragedy, a moratorium on climate change research is the only

responsible option for revealing and then restoring the broken science-society

contract. The other two options are seductive but offer false hope.

Links