INVERSE

- Tara Yarlagadda

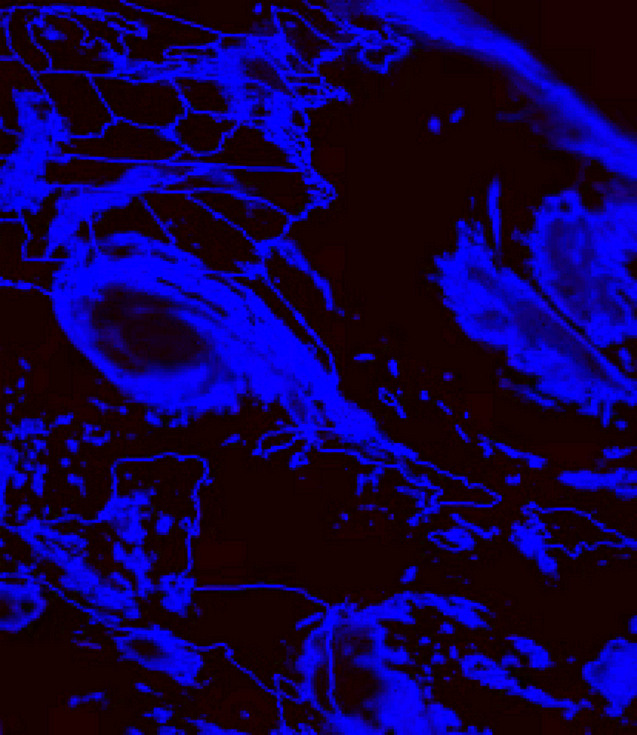

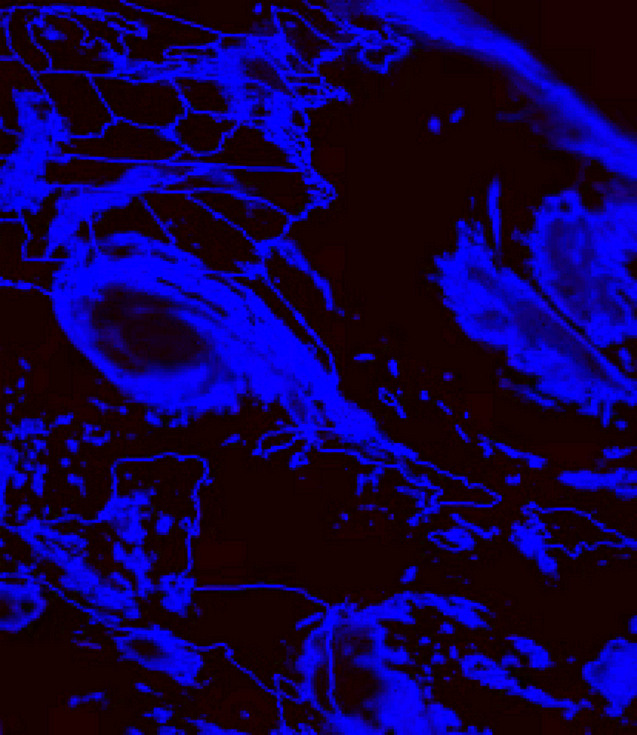

This year will be pivotal.

|

Stocktrek/Photodisc/Getty Images

|

Forget what you thought you knew about the

climate crisis.

In terms of weather, this year will be so much more extreme than

the past — but it could also be the year we take the path to change.

Every major climate moment in 2021 reveals the potential for

innovation, resilience, and actions that both individuals and governments can

take to ride out the coming storms.

It is impossible to put a positive spin on the

extreme weather events

that marked 2021, and which will only become more frequent in the coming years

due to global warming.

But as we get a New Year underway, it is

worth examining

11 of the wildest climate takeaways of 2021 —

and the helpful steps forward they reveal that can help us address the crisis

head-on.

In brief, our shortlist comes down to these 11 lessons:

11. Trees’ growing seasons are changing

10. Far more fossil fuels need to stay underground than we

thought

9. Climate change needs a messaging reboot

8. The permafrost is more critical to the future of Earth than

you know

7. We now know when polar bears will disappear — unless we

act

6. The fate of the Arctic and the western United States are

connected

5. A maligned animal could help solve global warming

4. Cities need to change for one vital reason

3. The Amazon rainforest may not save us

2. Animals are evolving to cope

1. It’s not so simple as taking a year off from air travel

Let’s dive into each of these lessons...

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

● ● ●

11. Trees’ growth seasons are changing — and making allergies worse

Climate change affects trees and plant life — and, in turn,

our seasonal allergies. According to a February 2021 study, warming temperatures lengthen the spring

pollen season, in turn worsening the symptoms of seasonal allergies and other

respiratory issues.

A second study suggests warmer temperatures in

cities, in particular, are causing trees’ leaves to

turn green earlier

in spring. The autumnal leaf color change occurs later, in contrast

— again, likely exacerbating allergies.

Here’s the solution

Trees have been shown to

cool cities down, and advocates have encouraged tree planting to offset carbon dioxide

emissions contributing to global warming.

But these studies and

other research suggest we need to be more conscientious about where, when, and

how we go about planting trees in cities, taking into account how their growing

season is affected by urban environments.

The best thing you can do to minimize pollen exposure is to avoid outdoor

activities early in the morning — when pollen counts are highest — and to close

your window at night.

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

● ● ●

10. Fossil fuels need to stay in the ground

|

A coal power station. Researchers say 90 percent of the world’s

coal must remain in the ground if we are to meet necessary climate

change targets. Getty

|

A coal power station. Researchers say 90 percent of the world’s coal must remain

in the ground if we are to meet necessary climate change targets.

Getty

To keep global temperatures from rising above 1.5 degrees Celsius above

pre-industrial levels — the ideal benchmark to avert climate catastrophe — in a

paper published earlier this year, a team of researchers

says

we have to keep the majority of the world’s fossil fuels in the ground. That

includes 97 percent of the coal in the United States.

Specifically, the researchers state:

-

Sixty percent of the world’s oil and methane gas needs to remain unextracted

- Ninety percent of the world’s coal needs to remain unextracted

Here’s the solution

We need to speed up the transition to

renewable energy.

To that end, the researchers give five specific suggestions to make the

transition toward renewable energy:

- Nix production subsidies for fossil fuels

- Tax the production of fossil fuels

-

Penalize companies that fail to comply with fossil-fuel regulations,

especially methane leaks

- Ban new fossil-fuel exploration

-

Institute international initiatives, like

a treaty

on the non-proliferation of fossil fuels

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

● ● ●

9. People care about climate change

Earlier this year, the United Nations released findings from the

People’s Climate Vote, the world’s largest survey on climate change thus far. It encompasses 1.2

million participants from 50 countries.

You can read

our full summary

of the key findings, but the biggest takeaway of all is people of all ages

recognize climate change is an emergency. Yet not everyone favored urgent

action, suggesting a lack of education around climate change issues — there

is also a clear generational difference in how people think about climate

change. According to the findings:

"Nearly 70 [percent] of under-18s said that climate change is a global

emergency, compared to 65 [percent] of those aged 18-35, 66 [percent] aged

36-59 and 58 [percent] of those aged over 60."

Here’s the solution

The report clearly states “more education is required even for those people who

are already concerned about climate change.” Organizations like NASA are on it —

the space agency currently offers climate change curriculum

resources

for U.S. schools.

The report also highlights four popular climate-change policies for governments

to aim toward:

- Conservation of forests and land (54 percent)

- Solar, wind, and renewable power (53 percent)

- Climate-friendly farming techniques (52 percent)

- Investing more in green businesses and jobs (50 percent)

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

● ● ●

8. The permafrost is an overlooked and critical factor in global

warming

|

Thawing of the permafrost is flooding forests in Siberia — and

exacerbating global warming. Getty

|

Thawing Siberian permafrost — a layer of soil that normally remains frozen

year-round — has unearthed the terrifying remains of

ancient creatures, but an even scarier thing is emerging from beneath the ice.

In 2021, scientists

concluded

policymakers, including at the UN, aren’t focusing enough on the emissions

released from the melting permafrost and Arctic wildfires. The researchers

predict carbon dioxide emissions from permafrost may increase by 30 percent by

the end of the century — a metric that isn’t being considered in climate change

conversations.

As a result, policymakers may be seriously underestimating the amount of fossil

fuel emissions we need to reduce to keep global warming in check.

Here’s the solution

Scientists need to warn policymakers of the imminent threat posed by permafrost

thaw and Arctic wildfires, especially ahead of key climate talks.

The UN wrapped up its climate change conference,

COP26,

earlier this year, but will reconvene in Egypt next year for further discussions

— the permafrost should be on the agenda.

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

● ● ●

7. When polar bears will disappear

|

It’s not too late to save the Arctic or the polar bears, but we

have to act now to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Getty

|

Scientists have been sounding the alarm on the threat melting Arctic ice poses

to polar bear habitats, but in 2021, they put an extinction date on this iconic

species — if we should fail to act on climate change.

Under a scenario of high greenhouse gas emissions, Arctic summer ice will

completely melt by 2100, killing off the ice-dependent polar bear as well.

Here’s the solution

If we can lower greenhouse gas emissions and global warming to below 2 degrees

Celsius Celsius above pre-industrial levels, summer ice — and polar bears — in

the Arctic will still have a fighting chance.

Countries can also establish protected marine reserves, like Canada’s

Tuvaijuittuq Marine Protected Area, to reduce pollutants that harm sea ice.

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

● ● ●

6. Ice melt fuels extreme weather

In 2021,

wildfires raged

out of control from California to Greece. Longer and drier fire seasons, fueled

by climate-change-driven drought, were to blame. But scientists also recently

identified a devastating link between wildfires and a surprising place: the

Arctic.

Using scientific models, researchers demonstrated how melting Arctic sea ice

could be linked to hotter and drier weather in the western U.S. through air

circulation patterns. So, melting Arctic sea ice could indicate a greater risk

of wildfires in this region.

Here’s the solution

Researchers are hopeful that their findings can inform better fire management in

the western U.S. since they can track the loss of Arctic sea ice a few months in

advance of fires in the U.S. and prevent wildfires from occurring in the first

place.

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

● ● ●

5. Cows may have a silver-lining

Scientists have

long recognized

the devastating effect of cows’ belches and farts, which release methane into

the atmosphere.

But what if we could harness cows to help save us from the climate crisis? It’s

a radical idea, but two recent pieces of research suggest it’s not a completely

farfetched idea.

Here’s the solution

The first study proposes potty training cows to urinate in specific areas,

thereby limiting the flow of nitrous oxide from their pee. Nitrous oxide is a

greenhouse gas that is 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide, so this

bizarre experiment could have seriously positive results for the climate.

The second study tackles the problem of plastic recycling using cows, or,

rather, their guts.

Single-use plastic products

clog our landfills, and their production

contributes to global warming. Researchers

found

that bacterial enzymes in the cow’s rumen are very good at decomposing plastic.

Don’t worry — this doesn’t mean we’ll feed plastic to cows. Instead, researchers

suggest acquiring cow rumen from slaughterhouses and using their bacterial

enzymes to degrade plastic on a commercial scale.

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

● ● ●

4. Record-breaking heat hits multiple cities

2021 may go down as the first hottest year of the rest of our lives. Heatwaves

scorched much of the western US in June 2021, followed by

record-breaking

December temperatures.

Rising temperatures are one of the most keenly felt effects of

the climate crisis

this year — and cities are especially vulnerable due to the urban heat island

effect, which traps heat in asphalt. Researchers revealed

a map

showing which cities — such as Dhaka, Shanghai, and Baton Rouge — are greatest

at risk of deadly urban heat.

Here’s the solution

There are ways we can beat the heat. In parts of India,

climate-resilient cities

are getting ahead of heatwaves by painting white “cool roofs” that deflect

sunlight.

The UN also released a list of

six cities

that are using climate-friendly cooling methods. Among them is Paris, France,

which takes water from the Seine River, chills it, and runs it through pipes

surrounding buildings for cooler temperatures — an eco-friendly A/C

replacement.

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

● ● ●

3. Deforestation is turning the Amazon rainforest into a carbon emitter

|

Large swaths of the Amazon are being deforested for cattle

grazing, contributing to global warming. Getty

|

Environmentalists often refer to the Amazon as “the world’s lungs.”

Historically, it’s been one of the world’s largest carbon sinks — places that

absorb more carbon dioxide than they emit, helping reduce the impact of global

warming.

But due to rampant deforestation in the Amazon, the rainforest has turned from

one of the world’s largest carbon sinks to one of its biggest emitters. Two

shocking findings from earlier this year confirm this trend.

First, a study published in

Nature found the rainforest is now emitting

0.3 billion tons

of carbon into the air each year. Second, a study published in

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found deforestation and

climate-change-related drought is

significantly reducing the Amazon’s role

as a carbon sink.

Here’s the solution

We need to halt deforestation in the Amazon — fast.

World leaders at the UN’s

COP26 conference

announced a landmark initiative to end deforestation by 2030, which will,

presumably, focus heavily on the Amazon. Brazil, which controls much of the

Amazon, also signed this pledge.

Meanwhile, consumers can consider if products they consume are resulting in

deforestation in the Amazon. Trees in the Amazon are commonly cut down to

make room for

soy production and grazing for cattle, AKA, beef.

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

● ● ●

2. Animals are adapting to climate change

|

Ribbit, ribbit. Climate change is here. Getty

|

Frogs

are aging rapidly due to climate change. Animals like rabbits are

evolving longer ears

to cope with hotter temperatures.

Some birds in the Amazon are b

ecoming smaller

to cope with drier conditions. Other birds, who could theoretically help save

plants from the climate crisis by transporting their seeds to cooler northern

climates, are counterintuitively

flying south

to hotter environments instead.

In short: animals are transforming and migrating in a number

of ways due to climate change — and not all of them are good.

Here’s the solution

With more animals on the move to escape warmer environments during climate

change,

some scientists

are saying we need to reconsider how we consider so-called “invasive” species

that are not native to a region.

To be clear: Invasive species are no joke, and can significantly reshape

ecosystems around the world, even in remote places

like Antarctica.

But as climate change forces animals to move north, some ecologists are

suggesting these animals are not invasive species, but, rather, climate

refugees. Other scientists

suggest

invasive species can be reduced or managed, but don’t need to be eliminated

entirely.

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

● ● ●

1. Greenhouse gas emissions are up — but there is a silver lining

|

Fossil fuel emissions spiked once again in 2021, but emissions

may have overall flattened over the past decade. Shifts in

electric vehicles and transportation could help reduce

greenhouse gas emissions in the near future. Getty

|

Despite greenhouse gas emissions briefly plummeting in spring 2020 due to

worldwide lockdowns, by early 2021, NASA’s early 2021

climate data

shows that global warming continued unabated, making the past decade the hottest

one on record.

As lockdowns ended and global consumption returned, experts predicted that

humans will emit

36.4 gigatons

of carbon dioxide in 2021. According to the

Global Carbon Project, carbon dioxide levels rebounded by 4.9 percent in 2021, with India and China

seeing particularly large spikes in coal.

On a slightly positive note: Emissions from the oil industry are lower in 2021

than 2019, and the researchers suggest that overall carbon dioxide emissions may

have flattened over the past decade, though these results are still

preliminary.

Here’s the solution

The message from climate scientists is loud and clear: We need to shift

away from fossil fuels as quickly as possible to save our planet from

catastrophe.

On the political level, leaders recently came together at the

UN COP26 climate conference

to agree to several landmark agreements on reducing fossil fuels, from creating

a “Beyond Oil & Gas Alliance” to a global pledge to reduce methane — a

significant contributor to carbon emissions.

On a corporate and individual level, some of the most promising efforts to cut

fossil fuel emissions are coming in the field of transportation, which accounted

for

29 percent

of 2019 greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S.

Numerous

reports

suggest electric vehicles are nearing a “tipping point” to make them more

affordable for the masses. As e-bike sales grew

145 percent

during 2020 and 2021, that

e-cycling trend

will also go a long way in taking fossil fuel-guzzling cars off the road.

Links