Rolling Stone - Bill McKibben

It hurts to be personally attacked in a movie. It hurts more to see a movement divided

|

Jeff Chiu/AP/Shutterstock; Craig Lassig/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

|

If you’re looking for a little distraction from the news of the

pandemic — something a little gossipy, but with a point at the end about

how change happens in the world — this essay may soak up a few minutes.

I’ll tell the story chronologically, starting a couple of weeks ago on the eve of the 50th

Earth Day.

I’d already recorded my part for the Earth Day Live webcast,

interviewing the great indigenous activists Joye Braum and Tara Houska

about their pipeline battles. And then the news arrived that Oxford

University — the most prestigious educational institution on planet

earth — had decided to divest from fossil fuels. It was one of the great

victories in that grinding eight-year campaign, which has become by

some measures the biggest anti-corporate fight in history, and I wrote a

quick email to Naomi Klein, who helped me cook it up, so that we could

gloat together just a bit. I was, it must be said, feeling pleased with

myself.

Ah, but pride goeth before a fall. In the next couple of hours came a

very different piece of news. People started writing to tell me that

the filmmaker

Michael Moore had just released a movie called

Planet of the Humans on YouTube.

That wasn’t entirely out of the blue — I’d been hearing rumors of the

film and its attacks on me since the summer before, and I’d taken them

seriously. Various colleagues and I had written to point out that they

were wrong; Naomi had in fact taken Moore aside in an MSNBC greenroom

and laid it all out, repeating the exchange with him while campaigning

in Iowa. But none of that had apparently worked; indeed, from what

people were now writing to tell me, I was the main foil of the film. I

put together a

quick response, and I hoped that it would blow over.

But it didn’t. Perhaps because everyone’s at home with not much to

do, lots of people watched it — millions by some counts. And I began to

hear from them. Here’s an email that arrived first thing Earth Day

morning: “

Happy Dead Earth Day. Time’s up Bill. You have been outed

for fraud. What a MASSIVE disappointment you are. Sell out. Hypocrite

beyond imagination. Biomass bullshit seller. Forest destroyer. How is it

possible you have led all of us down the same death trap road of false

hope? The YOUTH! How dare you! Shame on you!” More followed, to say

the least. (If you’re wondering whether it hurts to get this kind of

email, the answer is yes. In a time of a pandemic, it’s hard to feel too

much self-pity, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy to read someone

accusing you of betraying your own life’s work.)

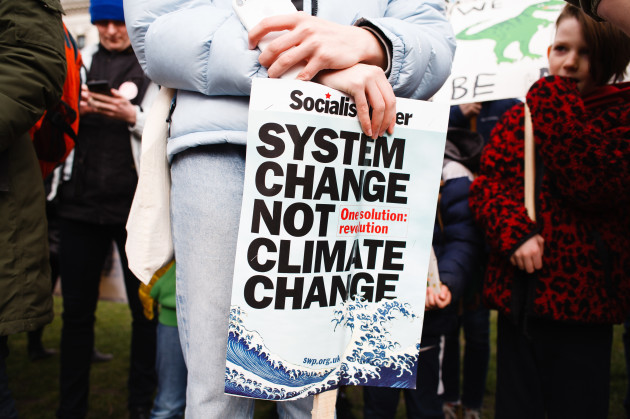

Basically, Moore and his colleagues have made a film attacking

renewable energy as a sham and arguing that the environmental movement

is just a tool of corporations trying to make money off green energy.

“One of the most dangerous things right now is the illusion that

alternative technologies, like wind and solar, are somehow different

from fossil fuels,” Ozzie Zehner, one of the film’s producers, tells the

camera. When visiting a solar facility, he insists: “You use more

fossil fuels to do this than you’re getting benefit from it. You would

have been better off just burning the fossil fuels.”

That’s not true, not in the least — the time it takes for a solar

panel to pay back the energy used to build it is well under four years.

Since it lasts three decades, it means 90 percent of the power it

produces is pollution-free, compared with zero percent of the power from

burning fossil fuels. It turns out that pretty much everything else

about the movie was wrong — there have been at least 24

debunkings, many of them painfully rigorous; as one scientist wrote in a particularly scathing

takedown, “

Planet of the Humans is deeply useless. Watch anything else.” Moore’s fellow filmmaker Josh Fox, in an

epic unraveling

of the film’s endless lies, got in one of the best shots: “Releasing

this on the eve of Earth Day’s 50th anniversary is like Bernie Sanders

endorsing Donald Trump while chugging hydroxychloroquine.”

Here’s long-time solar activist (and, oh yeah, the guy who wrote “

Heart of Gold“)

Neil Young: “The amount of damage this film tries to create (succeeding

in the VERY short term) will ultimately bring light to the real facts,

which are turning up everywhere in response to Michael Moore’s new

erroneous and headline grabbing TV publicity tour of misinformation.

A very damaging film to the human struggle for a better way of living, Moore’s film completely destroys whatever reputation he has earned so far.”

But enough about the future of humanity. Let’s talk about me, since I

got to be the stand-in for “corporate environmentalism” for much of the

film. Cherry-picking a few clips culled from the approximately ten

zillion interviews, speeches, and panels I’ve engaged in these past

decades, the filmmaker made two basic points. One, that I was a big

proponent of biomass energy — that is, burning trees to generate power.

Two, that I was a key part of “green capitalism,” trying somehow to

profit from selling people on the false promise of solar and wind power.

The first has at least a kernel of — not truth, but history. Almost

two decades ago, wonderful students at the rural Vermont college where I

teach proposed that the oil-burning heat plant be replaced with one

that burned woodchips. I thought it was a good idea, and when it finally

came to pass in 2009, I spoke at its inauguration. This was not a weird

idea — at the time, most environmentalists thought likewise, because as

new trees grow back in place of the ones that have been cut, they will

soak up the carbon released in the burning. “At that point I would have

done the same,” Bill Moomaw, who is one of the most eminent researchers

in the field, put it. “Because we hadn’t done the math yet.” But as

scientists

did begin to do the math, a different truth emerged: Burning trees put a puff of carbon into air

now,

which is when the climate system is breaking. That this carbon may be

sucked up a generation hence is therefore not much help. And as that

science emerged, I changed my mind, becoming an outspoken opponent of

biomass. (Something else happened too: the efficiency of solar and wind

power soared, meaning there was ever less need to burn

anything. The

film’s attacks on renewable energy are antique, dating from a decade

ago, when a solar panel cost 10 times what it does today; engineers have

since done their job, making renewable energy the cheapest way to

generate power on our planet.)

As for the second charge, it’s simply a lie — indeed, it’s the kind

of breathtaking black-is-white lie that’s come to characterize our

public life at least since Vietnam veteran John Kerry was accused by the

right wing of committing treason. I have never taken a penny from green

energy companies or mutual funds or anyone else with a role in these

fights. I’ve never been paid by environmental groups either, not even

350.org, which I founded and which I’ve given all I have to give. I’ve

written

books and given endless

talks challenging the prevailing ideas about economic growth, and I’ve run

campaigns designed entirely to cut consumption.

Let me speak as plainly as I know how. When it comes to me, it’s not that

Planet of the Humans

overstates the case, or gets it partly wrong, or opens an argument

worth having: it is a sewer. I’ll finish with just the smallest example:

In the credits, it defensively claims that I began opposing biomass

only last year, in response to news of this film. In fact, as we wrote

the filmmakers on numerous occasions, I’ve been on the record about the

topic for years. Here, for instance, is a

piece

from 2016 with the not very subtle title “Burning Trees for Electricity

Is a Bad Idea.” Please read it. When you do, you will see that the

filmmakers didn’t just engage in bad journalism (though they surely

did), they acted

in bad faith. They didn’t just behave dishonestly (though they surely did), they behaved

dishonorably.

I’m aware that in our current salty era those words may sound mild, but

in my lexicon they are the strongest possible epithets.

A reasonable question: Given that the film has been so thoroughly debunked, can it really cause problems?

I’ve spent the past three decades, ever since I wrote

The End of Nature

at the age of 28, deeply committed to realism: no fantasy, no spin, no

wish will help us deal with the basic molecular structure of carbon

dioxide. That commitment to reality has to carry over into every part of

one’s life. So, realistically, most of the millions of people who watch

this film will not read the careful debunkings. Most of them will

assume, in the way we all do when we watch something, that there must be

something there, it must be half true anyway. (That’s why propaganda is

effective). To give one more small example from my email, here’s a note

I received the other day:

Stop killing trees you lying murderer.

Forests are life. you are killing us all.

You can change your stance and turn back the tide of destruction

you unleashed… or perhaps just go throw yourself in a fire and go down

as one of the worst humans to ever exist.

Straight up evil.

When I wrote back (and I always write back, as politely as I know

how), explaining what I’ve explained in this essay, the writer’s reply

was: “I have read your dribble and am glad someone has finally called

you out for the puppet you are.”

I don’t think most people are that mean-spirited (or maybe I just

hope not) and of course dozens of friends within the climate movement

wrote to express their solidarity and love. But I have no doubt that

many of the people who’ve seen the film are, at the least, disheartened.

Here’s what one hard-working climate activist wrote me from Montana:

“The problem is, this movie is all over the place and is already causing

divisions and conflicts in climate action groups that I’m involved in —

it’s like they detonated a bomb in the center of the climate action

movement.” Which I’m sure is true (and I’m sure it’s why the film has

been so well-received at Breitbart and every other climate-denier

operation on the planet).

Which may well mean that for now — maybe for a long time — my work

will be at least somewhat compromised and less effective, because my

work is mostly about trying to build that movement, to make it larger

and more unified. Yes, there are days (and more of them than I would

have expected) when it’s about

going to jail,

but mostly it’s been a long, long process of reaching out and talking

to groups and people — helping them raise consciousness (and sometimes

helping them raise money). I’ve spent a very large percentage of my life

in high school auditoriums and at Rotary lunches; I’ve traveled to

every corner of the world, and in recent years, as the technology

improved, I’ve traveled too by low-carbon Skype and Zoom. (Pandemic

communications is old-school to me; for some reason I now forget, my

invaluable colleague Vanessa Arcara assembled a

list

of the virtual talks I gave in one stretch of 2015-16, which will give

you a sense of what my days are like). But if those visits and talks end

up igniting suspicion and controversy, then they’re obviously less

useful. I want to help important organizing, not disrupt it.

I’m used to attacks, of course. The oil industry has been after me

for decades, and some of their tactics have been far worse than Moore’s —

the period when they assigned videographers to literally follow me

whenever I set out the door was another low point in my life, but I

didn’t complain

until

it seemed like they were doing the same to my daughter. I’ve gotten

used to an endless and creative series of death threats — each one jolts

you for a moment, but clearly, since I’m still here, most of them are

not serious. And again, I’ve only

complained

once, when they were bandying about my home address and particular

methods of execution on well-trafficked websites. But those kind of

attacks don’t confuse and divide environmentalists; if anything, they do

the opposite. They’re a punch in the nose, which turns out to be far

less damaging than a stab in the back.

And I think this leads to the larger point, about what’s useful for movements and what isn’t.

I’m going to begin by boasting for a moment, if only to make myself

feel a little better: Here’s what I’d like people to recall from my work

these past years, as opposed to the notion that I am a forest-raping

sellout. See if you can figure out what every item on this short list

has in common.

- My role in helping found and build an actual climate movement. I

decided at a certain point that we weren’t in an argument over global

warming (we’d won that), but that we were in a fight. And the other side

— the fossil fuel industry — was so powerful they were going to win

unless we built some power of our own. Hence my decision to go beyond

writing and to try to learn how to organize. In 2007, with my seven

original undergraduate collaborators, we formed Step It Up and found

people to organize 1,500 simultaneous demonstrations across the U.S.;

two years later, at the start of 350.org, the numbers were 5,200 rallies

in 181 countries.

- My role in helping nationalize the fight over the Keystone XL

pipeline, and in the process lay the seedbed for much of the ‘keep it in

the ground’ work that has led to challenges of fossil fuel

infrastructure around the world.

- My role in helping launch the divestment fight, with a piece of writing and with the Do the Math campaign around the U.S. and then Europe and the antipodes. (Here’s the movie from that; I think it’s better than Moore’s). We’re currently at $14 trillion in endowments and portfolios that have divested.

- My role in helping solidify and unify the newer fight against the

banks, asset managers, and insurance companies that fund the fossil fuel

movement — the StopTheMoneyPipeline.com effort that is fighting pitched battles right now with Chase Bank, Liberty Mutual, and BlackRock.

The thing that unites these four things is the word “helping.” So

many others have fought just as hard. If I started listing names I

literally would never stop; the pleasure has been in the teamwork and

collaboration.

And that’s the point: Movements only really work if they grow, if

they build. If they move. And that’s almost always an additive process.

The trick, I think, is figuring out how to make it possible for more

people to join in. When we started 350.org, we gave out the logo to

anyone. It was like a potluck supper; if you organized a little

demonstration in your town, you were a part. (One of the early protests

we were proudest of involved exactly one woman: an Iranian in a

headscarf who worked her way through half a dozen army checkpoints to

hold up a sign). The Keystone fight was well underway when we came on

board — indigenous groups and Midwest ranchers had been fighting hard —

but we helped to create ways to let anyone anywhere join in, framing it

as a fight about

climate change

as well as land. Divestment, similarly: not everyone has a coal mine in

their backyard, but everyone’s connected through a school or a church

or a pension to a pot of money.

Banks may be the best example:

Chase has tens of millions of credit cards out there. Or, to take the

example of the movie, biomass: Thank heaven for campaigners like Danna

Smith and Mary Booth and Rachel Smolker, who built a movement to help

explain why this was a bad idea. It worked for me — I changed my mind,

which is what you want movements to do.

You can, in other words, change the zeitgeist if you get enough

people engaged — if they both see the crisis and feel like they have a

way in.

But that’s precisely what’s undercut when people operate as Moore has

with his film. The entirely predictable effect is to build cynicism,

indeed a kind of nihilism. It’s to drive down turnout — not just in

elections, but in citizenship generally. If you tell a bunch of lies

about groups and leaders and as a result people don’t trust them, who

benefits?

To be clear, I doubt that was Moore’s goal. I think his goal was to

build his brand a little more, as an edgy “truth teller” who will take

on “establishments.” (That he has, over time, become a millionaire

carnival barker who punches down, not up — well, that’s what brand

management is for). But the actual effect in the real world is entirely

predictable. That’s why Breitbart loves the movie. That’s why the

tar-sands guys in Alberta are chortling. “People are going ga-ga over

it,” Margareta Dovgal, a researcher with the pro-industry Canadian group

Resource Works, told

reporters. The message they’re taking from it is “we’re going to need fossil fuels for a long time to come.”

Actually, we won’t. We’ve dropped the price of sun and wind 90

percent in the last decade (since the days when Moore, et al. were

apparently collecting their data). As Stanford professor Marc Jacobson

has made clear, we could get much of the way there in relatively short

and affordable order, by building out panels and turbines, by making our

lives more efficient, by consuming less and differently. But that would

require breaking the political power of the fossil fuel industry, which

in turn would require a big movement, which in turn would require

coming together, not splitting apart.

It’s that kind of movement we’ve been trying to build for a long

time. I remember its first real gathering in force in the U.S., with

tens of thousands of us standing on the Mall in Washington on a bitter

February day in 2013 to demand an end to Keystone and other climate

action. “All I’ve ever wanted to see was a movement of people to stop

climate change,” I

told the crowd. “And now I’ve seen it.”

We did an immense amount of work to get to that moment, helping will a

movement into being. But from that moment on, for me it’s been mostly

gravy — the great pleasure of watching the movement grow and then

explode. Watching the kids who had built college divestment campaigns

graduate to form the Sunrise Movement and launch the Green New Deal.

Watching Extinction Rebellion start to shake whole cities. Watching the

emergence of the climate strikers — and getting to know

Greta Thunberg

and many of the 10,000 others like her across the world. In each case,

I’ve tried to help a little, largely just by amplifying their voices and

urging others to pay attention.

I remember very well the night that same autumn after an overflow

talk in Providence when my daughter, then a sophomore at Brown, said

something typically wise to me: “I think you should probably be less

famous in the years ahead.” I knew what she meant even as she said it,

because of course I’d already sensed a bit of it myself. It wasn’t that

she thought I was a bad leader — it was that we needed to build a

movement that was less attached to leaders in general (and probably

white male ones in particular) if we were going to attain the kind of

power we needed.

And so, even then I began consciously backing off, not in my work but

in my willingness to dominate the space. I stepped down as board chair

at 350.org, and really devoted myself to

introducing people to new leaders

from dozens of groups. So many of those leaders come from frontline

communities, indigenous communities — from the people already paying an

enormous price for the warming they did so little to cause. Their voices

are breaking through, and thank heaven: If you follow my twitter feed,

you’ll see that the most common word, after “heatwave”, is “thanks,”

offered to whoever is doing something useful and good. If you get the

chance to read the (free)

New Yorker climate newsletter

I started earlier this year, you’ll see the key feature is called

Passing the Mic: So far I’ve interviewed Nicole Poindexter, Jerome

Foster II, Mary Heglar, Ellen Dorsey, Thea Sebastian, Virginia Hanusik,

Tara Houska, Vann R. Newkirk II, and Christiana Figueres; this week Jane

Kleeb; next week Alice Arena, helping lead the fight against a new gas

pipeline across Massachusetts.

I think that one thing that defines those movements is their

adversaries — in this case the fossil fuel industry above all. And I

think the thing that weakens those movements is when they start trying

to identify adversaries within their ranks. Much has been made over the

years about the way that progressives eat their own, about circular

firing squads and the like. I think there’s truth to it: there’s a

collection of showmen like Moore who enjoy attracting attention to

themselves by endlessly picking fights. They’re generally not people who

actually try to organize, to build power, to bring people together.

That’s the real, and difficult, work — not purity tests or calling

people out, but calling them in. At least, that’s how it seems to me:

The battle to slow down global warming in the short time that physics

allots us requires ever bigger movements.

It’s been a great privilege to get to help build those movements. And

if I worry that my effectiveness has been compromised, it’s not a huge

worry, precisely because there are now so many others doing this work —

generations and generations of people who have grown up in this fight. I

think, more or less, we’re all headed in the right direction, that

people are getting the basic message right: conserve energy; replace

coal and gas and oil with wind and sun; break the political power of the

fossil fuel industry; demand just transitions for workers; build a

world that reduces ruinous inequality; and protect natural systems, both

because they’re glorious and so they can continue to soak up carbon. I

don’t know if we’re going to get this done in time — sometimes I kick

myself for taking too long to figure out we needed to start building

movements. But I know our chances are much improved if we do it

together.

Thanks so much to all who fight for all that matters. On we go.

Links