|

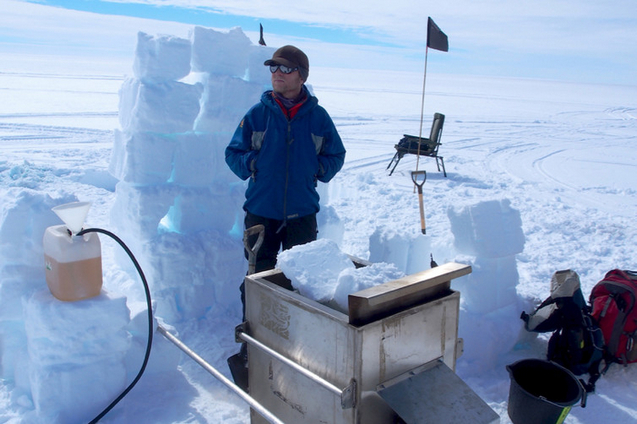

| NASA / John Sonntag |

|

|

|

|

| The ice shelves of the Antarctic peninsula. Note Larsen A and B have largely disappeared. AJ Cook & DG Vaughan, 2014, CC BY-SA |

Ice shelves are found where glaciers meet the ocean and the climate is cold enough to sustain the ice as it goes afloat. Located mostly around Antarctica, these floating platforms of ice a few hundred meters thick form natural barriers which slow the flow of glaciers into the ocean and thereby regulate sea level rise. In a warming world, ice shelves are of particular scientific interest because they are susceptible both to atmospheric warming from above and ocean warming from below.

Back in the 1890s, a Norwegian explorer named Carl Anton Larsen sailed south down the Antarctic Peninsula, a 1,000km long branch of the continent that points towards South America. Along the east coast he discovered the huge ice shelf which took his name.

For the following century, the shelf, or what we now know to be a set of distinct shelves – Larsen A, B, C and D – remained fairly stable. However the sudden disintegrations of Larsen A and B in 1995 and 2002 respectively, and the ongoing speed-up of glaciers which fed them, focused scientific interest on their much larger neighbour, Larsen C, the fourth biggest ice shelf in Antarctica.

|

|

|

Nature at work

The development of rifts and the calving of icebergs is part of the natural cycle of an ice shelf. What makes this iceberg unusual is its size – at around 5,800 km² it’s the size of a small US state. There is also the concern that what remains of Larsen C will be susceptible to the same fate as Larsen B, and collapse almost entirely.

|

| Larsen B once extended hundreds of kilometres over the ocean. Today, one of its glaciers runs straight into the sea. Armin Rose / shutterstock |

What is not disputed by scientists is that it will take many years to know what will happen to the remainder of Larsen C as it begins to adapt to its new shape, and as the iceberg gradually drifts away and breaks up. There will certainly be no imminent collapse, and unquestionably no direct effect on sea level because the iceberg is already afloat and displacing its own weight in seawater.

|

| VIDEO LINK |

|

| VIDEO LINK |

Is this a climate change signal?

This event has also been widely but over-simplistically linked to climate change. This is not surprising because notable changes in the earth’s glaciers and ice sheets are normally associated with rising environmental temperatures. The collapses of Larsen A and B have previously been linked to regional warming, and the iceberg calving will leave Larsen C at its most retreated position in records going back over a hundred years.

However, in satellite images from the 1980s, the rift was already clearly a long-established feature, and there is no direct evidence to link its recent growth to either atmospheric warming, which is not felt deep enough within the ice shelf, or ocean warming, which is an unlikely source of change given that most of Larsen C has recently been thickening. It is probably too early to blame this event directly on human-generated climate change.

Links

- Iceberg twice size of Luxembourg breaks off Antarctic ice shelf

- Giant Antarctic iceberg 'hanging by a thread', say scientists

- Giant iceberg poised to break off from Antarctic shelf

- Antarctic ice thicker than previously thought, study finds

- B31: huge Antarctic iceberg headed for open ocean

- Scientists re-trace steps of great Antarctic explorer Douglas Mawson

- Iceberg half the size of Greater London calves off Antarctic glacier

- Scientists hold breath over polar ice satellite launch after 2005 crash

- Giant Antarctic iceberg could affect global ocean circulation

No comments:

Post a Comment