|

Coal power needs to drop to below 2 per cent of current usage to keep the temperature rise to 1.5 degrees. (Flickr: UniversityBlogSpot)

|

Key points

|

In a report authored by more than 90 scientists, and pulling together thousands of pieces of climate research, the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) said global emissions of greenhouse gas pollution must reach zero by about 2050 in order to stop global warming at 1.5 degrees Celsius.

At current rates, they said 1.5C would be breached as early as 2040, and 2C would be breached in the 2060s.

If that happens, temperatures over many land regions would increase by double that amount. And at 2C of warming, experts said the world would risk hitting "tipping points", setting the world to uncontrollable temperatures.

With the world already 1C warmer than pre-industrial times, experts said this report, released by the IPCC in Incheon, Korea, was likely the last warning before it would be impossible to keep warming at 1.5C.

"We're not on track, we're currently heading for about 3 degrees to 4 degrees of warming by 2100," report contributor Professor Mark Howden from ANU said.

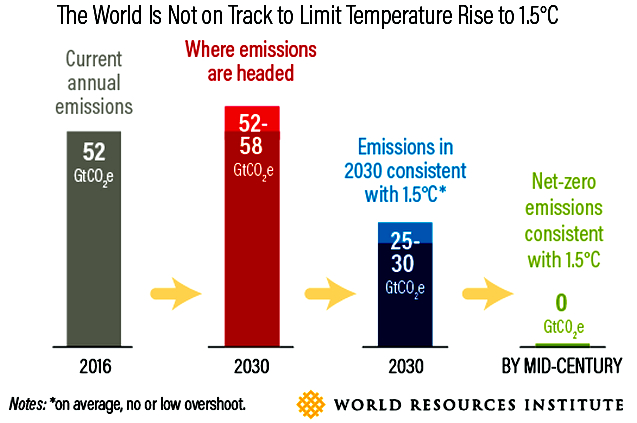

"To limit temperature change to 1.5 degrees we have to strongly reduce carbon dioxide emissions. They have to decline about 45 per cent by 2030 and they have to reach zero by 2050.

Coral reefs are expected to decline by a further 70 to 90 per cent under 1.5C, but that rises to more than 99 per cent reef loss as temperature rises hit 2C.

In Australia, that means the vast majority of the Great Barrier Reef will undergo significant upheaval or collapse.

Combined with increased ocean acidification due to higher carbon dioxide concentrations, this is expected to heavily affect fish stocks and diversity.

A rise of 2C would mean three times as much of the earth's terrestrial ecosystems would undergo transformations compared to a rise of 1.5C, significantly increasing species extinctions.

|

We'll see an ice-free Arctic every 10 years under 2 degrees of warming. (UN Photo: Mark Garten)

|

A 2C rise would mean an extra 10 centimetres of sea-level rise by the end of the century, affecting an extra 10 million people. And it would double the number of people experiencing water scarcity.

And we would be hit with more extreme hot weather events in every part of the world, more floods in most, and more drought in some.

Those extreme events would be "far worse" as temperature increases go beyond 1.5C, according to Will Steffen from ANU's Climate Change Institute.

"Loss of the Amazon forests, melting of the permafrost, loss of ice in West Antarctic and Greenland, they are much riskier at 2 degrees than they are at 1.5," Professor Steffen said.

"They could lead to a tipping cascade where the system will get hotter and hotter even if we bring our emissions down."

Coal use needs to drop to '0 to 2 per cent': expert

In 2015, almost every country agreed to stop global warming at "well below" 2C under the Paris Agreement, and to try to limit it to just 1.5C.

But 1.5C is a global average, which is dampened by ocean temperatures and doesn't represent regional extremes, according to report contributor Jatin Kala from Murdoch University.

"Even some world leaders seem to think that 1.5 degrees is a small number, why do we care?" Dr Kala said.

"Warming over the land is at a higher level of magnitude. We care because when the global average is 1.5 degrees warmer, that means that several regions of the world are warming at much higher magnitudes — they'll be a lot warmer than 1.5."

To limit warming to 1.5C, there needed to be "deep changes in all aspects of society", according to Professor Howden.

"It does actually require major transformations in many aspects of society and to do those transitions, the next 10 years is critical," Professor Howden said.

"Electricity will have to be supplied by renewables on a global basis by the tune of about 70 to 85 per cent of electricity supply.

"Coal would have to drop to within 0 and 2 per cent of existing usage, and gas down to about 8 per cent of existing usage, and only if there was carbon dioxide capture and storage associated."

Although renewables like solar and wind are rapidly disrupting energy systems around the world, freight, aviation, shipping and industry are lagging behind in emissions reduction.

LNG processing is contributing significant greenhouse gas emissions and carbon sequestration is "virtually not happening", according to contributor Peter Newman from Curtin University.

But Professor Newman said there was some movement in the right direction.

"Electric vehicles are rapidly happening around the world," he said.

"[In Australia], the industrial systems are not good, but the land systems however are a good sign. There has been significant reforesting of the landscape."

'No easy way' to avoid reaching tipping point

There is a limit to the amount of carbon we can pump into the atmosphere, after which point restricting the temperature rise to 1.5C becomes impossible.

Researchers say at current emissions rates the world will hit that point between 10 and 14 years from now. Overshooting that mark means that our only option may be to employ "experimental and untested" carbon removal technologies.

These technologies are yet to be proven at scale, and critics say they have been used to fuel "magical thinking".

"There isn't an easy way to do this," said Associate Professor Bronwyn Hayward from the University of Canterbury.

"If we don't make these really difficult, unprecedented cuts now, there's fewer options for sustainable development. We'll be forced to rely more on these unproven, risky and potentially socially undesirable forms of carbon removal."

Minister for the Environment Melissa Price released a statement in response to the report, in which she said the Government was "particularly concerned" about the implications for coral reefs.

"More than ever this report shows the necessity of the Morrison Government's $444 million investment in the Great Barrier Reef's management," the Minister said.

"While Australia only contributes about 1 per cent of global emissions, we will deliver on our commitment to reduce emissions by 26 to 28 per cent of 2005 levels by 2030."

Labor has vowed to take back the Government's $444 million Great Barrier Reef Foundation funding — which was granted without a competitive tender process and without the foundation asking for it — if it wins the next federal election.

Ms Price's statement also said that Australia's emissions intensity is at its lowest level for 28 years. But according to the Government's own data, Australia's overall emissions have increased for the third year in a row.

The Government was criticised for sitting on that data for nearly two months, before releasing it on a Friday afternoon on the eve of football grand finals and a long weekend.

Links

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Report: 1.5˚C

- Coal Power Finished By 2050 If Temperature Increase Kept To 1.5 Degrees: IPCC

- The world has just over a decade to get climate change under control, U.N. scientists say

- IPCC 1.5 C degree report points to high stakes of climate inaction

- UN warns paradigm shift needed to avert global climate chaos

- World Resources Report: Creating a Sustainable Food Future

- Low-Carbon Growth Is a $26 Trillion Opportunity. Here Are 4 Ways to Seize It.

- Half a Degree and a World Apart: The Difference in Climate Impacts Between 1.5 and 2˚C of Warming

- 6 Ways to Remove Carbon Pollution from the Sky

- Forget Paris: Australia needs to stop pretending we're tackling climate change

- Here's why the majority of green turtles in north Queensland are female

- 2017 was third warmest year on record for globe, scientists say