The Earth's glaciers are in rapid retreat.

New results relying on five decades of satellite observations show extensive changes to glaciers at the Earth's north and south poles, a result of global warming.

Much of the data comes courtesy of the long-running Landsat mission, which is a series of Earth observation satellites managed by NASA and the United States Geological Survey. Having decades of data from a single line of similar satellites makes it much easier to see change over time. But other satellites are spotting changes as well, sometimes on timescales as short as a year or two.

|

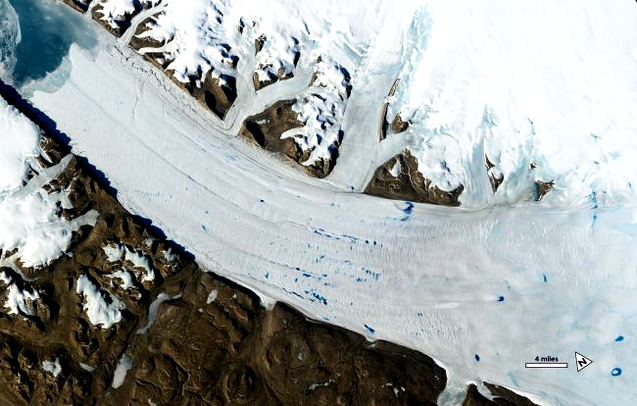

| Meltwater pools on the surface of Petermann Glacier in Greenland as seen by Landsat in June 2019. (Image credit: NASA/USGS) |

"We now have this long, detailed record that allows us to look at what's happened in Alaska," Fahnestock said in a NASA statement. "When you play these movies, you get a sense of how dynamic these systems are and how unsteady the ice flow is."

Glaciers respond to global warming in different ways. For example, Alaska's Columbia glacier was pretty stable when the first Landsat satellite peered at it in 1972. It began a quick retreat in the mid-1980s; it now is 12.4 miles (20 kilometers) upstream from its first observed position nearly 48 years ago. Meanwhile, the nearby Hubbard Glacier has only moved three miles (five km) in the same 48 years, but a 2019 image showed a large area in the glacier where ice broke off. That "calving embayment," as geologists term it, is likely a sign of rapid change on the horizon.

"That calving embayment is the first sign of weakness from Hubbard glacier in almost 50 years — it's been advancing through the historical record," Fahnestock said, warning that the Columbia glacier showed similar signs of weakening before its rapid retreat decades ago.

The NASA-USGS Landsat program has been keeping its eyes on Earth's glaciers and ice sheets since 1972.

Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

Michalea King, a doctoral student in earth sciences at Ohio State University, examined similar Landsat images from Greenland as far back as 1985 to see how global warming affected 200 glaciers there. These glaciers have retreated an average of three miles (five km) over the period of satellite observations that King studied.

"These glaciers are calving more ice into the ocean than they were in the past," King said in the same statement. "There is a very clear relationship between the retreat, and increasing ice mass losses from these glaciers, during the 1985-through-present record."

The glacial retreat is also causing different sorts of lakes to appear over time on the surface of the glacier and underground. James Lea, a glaciologist at the University of Liverpool in the United Kingdom, found surface meltwater lakes on Greenland glaciers of up to three miles (five km) across. Lea used measurements gathered by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on the NASA-led Terra satellite for every day of every melt season over the last 20 years.

"We looked at how many lakes there are per year across the ice sheet and found an increasing trend over the last 20 years: a 27% increase in lakes," Lea said in the same statement. "We're also getting more and more lakes at higher elevations — areas that we weren't expecting to see lakes in until 2050 or 2060."

The change is so rapid that sometimes differences show up in just a year or two. For example, Devon Dunmire of the University of Colorado, Boulder, used microwave radar images from the European Space Agency's Sentinel-1 satellite to peer beneath the ice. Dunmire spotted lakes in the George VI and Wilkins ice shelves near the Antarctica peninsula, including a few that remained liquid during winter.

"Not much is known about distribution and quantity of these subsurface lakes, but this water appears to be prevalent on the ice shelf near the Antarctic peninsula," said Dunmire, who is a graduate student in atmospheric and oceanic sciences, in the same statement. "It's an important component to understand, because meltwater has been shown to destabilize ice shelves."

The scientists presented their work at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco on Dec. 9.

Links

- Ice in Motion: Satellites Capture Decades of Change

- Huge Iceberg Poised to Break Off Antarctica's Pine Island Glacier

- Which Melting Glacier Threatens Your City the Most? NASA Tool Can Tell You

- Fastest-Thinning Greenland Glacier Threw NASA Scientists for a Loop. It's Actually Growing.

- Photos: Gorgeous Landscapes Hidden Beneath Polar Seas

- Astrophotographer Visits 'Alien World' on Earth in Spectacular Photo

- Images: Greenland's Gorgeous Glaciers

- Icy Images: Antarctica Will Amaze You in Incredible Aerial Views

No comments:

Post a Comment