A European start-up uses satellite data to pinpoint individual sources of abnormal methane concentration.

|

|

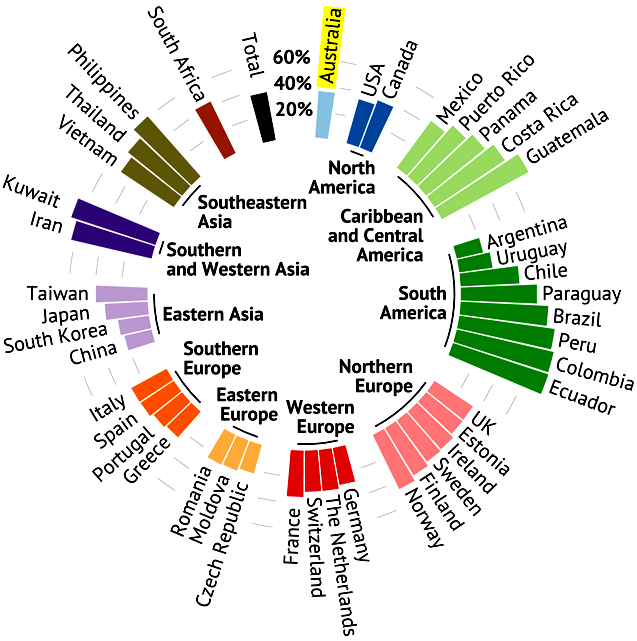

World map of abnormal methane emissions, thanks to a tech start-up

and satellite data.

Image: Kayrros |

- Just 100 sources of methane emit 20 megatons each year.

- Thanks to satellite data, individual culprits can now be found.

- The new tech could be used to police 'abnormal' methane emissions.

Significant contributor to global warming

|

|

Nodding donkey in Midland, Texas. The oil and gas industry

is a major emitter of methane. Image: Eric Kounce TexasRaiser, public domain

|

Because it absorbs the sun's heat even more efficiently than CO2, it's a significant contributor to global warming.

The first step to fight the rise in methane emissions is to track who's doing it. That's just become a lot easier. Paris-based tech start-up Kayrros can now find individual sources of abnormal methane emissions, all across the world.

That's a first, and it's made possible by data from the Copernicus Sentinel-5P satellite.

Developed by the European Space Agency (ESA) and launched in 2017, the British-built Sentinel-5 Precursor (Sentinel-5P) is the first satellite of the Copernicus program dedicated to monitoring air pollution, thanks to a spectrometer called Tropomi (short for Tropospheric Monitoring Instrument).

With a resolution of about 50 km2, this Dutch-built instrument can monitor atmospheric levels of aerosols, sulphur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), carbon monoxide (CO), formaldehyde (CH2O), ozone (O3) and methane (CH4).

High-volume methane leaks

|

|

Abnormal methane concentrations in 2019 – often found in

regions of the world producing or processing oil and gas.

Data provided by the Copernicus program, processed by

Kayrros. Image: Kayrros

|

Tropomi also offers the most detailed monitoring of methane emissions presently available.

Combining that data with other input from older-model Copernicus satellites Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2, and from other sources (including ground sensors, position tracking and even social media), Kayrros scientists can identify the size, potency, and location of abnormal methane leaks around the world.

According to Kayrros, there are around 100 high-volume methane leaks active around the world at any given time.

Together, they release about 20 megatons of methane per year. About half of that volume is associated with mining for oil, gas or coal, or other heavy industries.

Together, that amount of methane per annum is equivalent to CO2 emissions of France and Germany combined.

So, how precise is the Kayrros method? Here's a recent case study.

Plume over the Permian Basin

|

|

Image: Kayrros |

Sitting on top of a part of the Mid-Continent Oil Field, the Basin's surface is dotted with hundreds of oil wells. Yet with a little help from Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2, Copernicus-5P managed to find the exact location, and the individual culprit.

For the first time, Kayrros tech and Copernicus-5P data make it possible to detect abnormal methane emissions in real time.

Not only will this increase the precision of methane emission estimates, it will also allow regulators to find and fine the exact culprits, and if necessary, shut down their operations.

Found: the culprit

|

|

Image: Kayrros |

- (AU) Methane Released In Gas Production Means Australia's Emissions May Be 10% Higher Than Reported

- (NY Times) Halting The Vast Release Of Methane Is Critical For Climate, U.N. Says

- NASA Just Released The First Direct Evidence That Humans Are Causing Climate Change

- (USA New Yorker) It’s Time To Kick Gas

- Land In Russia’s Arctic Blows ‘Like a Bottle Of Champagne’

- Gridded maps of geological methane emissions and their isotopic signature

- Artificial photosynthesis produces 'green methane'

- European Space Agency: Mapping methane emissions on a global scale